“Once there were a people so wealthy, plump, and sleek that they drank sea lion oil straight and didn’t have to look for food all winter long. They danced and sang and recited stories instead. These people’s upriver neighbors bent under ninety-pound packs. These people just carried their big boat down to their river, piled in several tons of trade goods ( cranberry preserves, smoked salmon, dried clams, six or seven kinds of vegetables, fur robes, and arrow-proof battle armor ) and paddled a hundred miles or so up the river to trade.

They were not just rich but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

What to call these people is a problem. The name Wimah merely meant “Big River,” which was the same meaning all of the other three languages above the Chin on the river called it. But the people had no name at all for themselves. Each village had a name, and there were names for groups of villages that spoke the same dialect, but each village was really separate, indeed each family was separate, though inextricably connected by relationships to other families. A man might take his house planks and dependents, and paddle up to the next village, and then he was one of those people. As for a name for all those who spoke Chinookan languages, fifty or more winter villages strung along both banks of the lowest two hundred miles of the Columbia River, plus twenty-five miles up the Willamette River at the falls and the Clackamas River, and twenty miles north and south along the Pacific seacoast, for all those people the river people had no name, indeed hardly more than a memory that they must be related.

When the first European ship sailed into the river and anchored eight miles above the mouth, offshore from proud Qwatsamts, a three-row village, the mariners wanted to know what to call the people. One sailor asked some sort of question, in some approximation of language, pointing at the village. Something like, “What are these people called?” (Pointing, by the way, was dangerous and ill-mannered among these people.) A headman or spokesman responded Chinoak or Tsinuk or something like that. Forever after, the white people called the people in that village, and three or four others along the riverbank nearby, Chinook or Chinooks. (The river people at first called the strangers tlohonnipts, “those who float [or drift] ashore.”)

After a while, when they learned that the people upriver for a couple of hundred miles had roughly the same languages, the tlohonnipts called them Chinook, too. Years later, all canoe-paddling Indians on the North Pacific Coast were sometimes referred to as Chinooks. All that, based on no more than what some person answered when strangers impolitely pointed toward the village of long cedar-plank houses, row on row along the shore, which town they called Qwatsamts.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

In trade they were very like us, but in other ways they were utterly opposite. Our Western heritage contemplates a universe where there is one central God and all the subordinate creatures take their identities in relation to that over powering One. The Chinook believed the world a multiverse where everything was alive and had its own spirit. The powers of the spirits differed widely but there was no central all-powerful One.

The Chinook lived along the river for thousands of years. Then pale strangers floated ashore, and within forty years the Chinook were pretty much gone. All but a few in the center of their land disappeared, a great majority of those at the seacoast and Willamette Falls, a relatively smaller percentage at the eastern edge, up the Columbia River Gorge. In much of that area their culture was shattered.

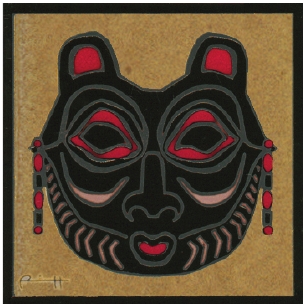

Tsagiglalal saw all this happen, from her rock at the uppermost end of the Chinook-occupied river. Tsagiglalal is a beautiful broad face, with luminous eyes and wide smile, her tongue thrust out, inscribed on rim-rock at the easternmost edge of the Chinook land. Coyote, their myth age trickster-hero, put her there to watch the people. “She Who Watches” they called her. She became a symbol of conscience and of death. “She sees you when you come,” they said, “she sees you when you go.”

What, if anything, did the long persistence and swift collapse of the Chinook mean? They were living so nicely. They had all they wanted and nobody to bother them, were wealthy and respected. Then, because of the skin of a sea mammal and a host of spirits too small to see, thousands of them died, their culture crumbled and the survivors were sent away in a cruel diaspora.

They didn’t sign away their rainy Eden or sell it, they didn’t die in warfare, or move to reservations, not until twenty-five years after the catastrophes that swept most of them away. It wasn’t smallpox that laid them low. Suddenly most them were simply gone. The Wapato Lowlands in particular were empty and silent. Did God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

This book is meant to remedy that lapse of memory. Naked Against The Rain, Far Shore Press, Portland, OR, 1999.

***

She Who Watches has also been called the stone Owl Woman who watches. Indian women have gone to the stone and knelt before it. They would say something like, “You who watch, please look into me and see my problem and help me to solve it.” A ray of light would come down to shine on the stone face then. After the woman goes to her teepee to sleep a dream would come telling her how to deal with the problem. Maybe that woman would go again to the stone and the ray of light would come down again on the stone, and the next dream would give even more detail as to how to solve the problem.

From: Tahmahnaw, The Bridge of the Gods, by Jim Attwell.