|

June 26th, 2011

On July 20, 1811, Duncan McDougal, Chief Factor for the Pacific Fur Company at Astoria, Oregon, and Ilchee, daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook Tribe, married, becoming the first couple to be married in Astoria.

Washington Irving in his narrative Astoria (published in 1836) tells the tale:

“… M’Dougal, who appears to have been a man of a thousand projects, and of great, though somewhat irregular ambition, suddenly conceived the idea of seeking the hand of one of the native princesses, a daughter of the one-eyed potentate Com’comly, who held sway over the fishing tribe of the Chinooks, and had long supplied the factory with smelts and sturgeons. Some accounts give rather a romantic origin to this affair, tracing it to the stormy night when M’Dougal, in the course of an exploring expedition, was driven by stress of the weather to seek shelter in the royal abode of Com’comly. Then and there he was first struck with the charms of the piscatory (sic) princess, as she exerted herself to entertain her father’s guest.

The “Journal of Astoria,” however, which was kept under his own eye, records this union as a high state alliance, and great stroke of policy. The factory had to depend, in a great measure, on the Chinooks for provisions. They were at present friendly, but it was to be feared they would prove otherwise, should they discover the weakness and the exigencies of the post, and the intention to leave the country. This alliance, therefore, would infallibly rivet Com’comly to the interests of the Astorians, and with him the powerful tribe of the Chinooks. Be this as it may, and it is hard to fathom the real policy of governors and princes, M’Dougal dispatched two of the clerks as ambassadors extraordinary, to wait upon the one-eyed chieftain, and make overtures for the hand of his daughter.

The Chinooks, though not a very refined nation, have notions of matrimonial arrangements that would not disgrace the most refined sticklers for settlements and pin-money. The suitor repairs not to the bower of his mistress, but to her father’s lodge, and throws down a present at his feet. His wishes are then disclosed by some discreet friend employed by him for that purpose. If the suitor and his present find favor in the eyes of the father, he breaks the matter to his daughter, and inquires into the state of her inclinations. Should her answer be favorable, the suit is accepted and the lover has to make further presents to the father of horses, canoes, and other valuables, according to the beauty and merits of the bride; looking forward to a return in kind whenever they shall go to housekeeping.

We have more than once had occasion to speak of the shrewdness of Com’comly; but never was it exerted more adroitly than on this occasion. Com’comly was a great friend of M’Dougal, and pleased with the idea of having so distinguished a son-in-law; but so favorable an opportunity of benefiting his own fortune was not likely to occur a second time and he determined to make the most of it. Accordingly, the negotiation was protracted with true diplomatic skill. Conference after conference was held with the two ambassadors. Com’comly was extravagant in his terms; rating the charms of his daughter at the highest price, and indeed she is represented as having one of the flattest and most aristocratical (sic) heads in the tribe.

At length the preliminaries were all happily adjusted. On the 20th of July, early in the afternoon, a squadron of canoes crossed over from the village of the Chinooks, bearing the royal family of Com’comly, and all his court.

That worthy sachem landed in princely state, arrayed in a bright blue blanket and red breech clout, with an extra quantity of paint and feathers, attended by a train of half-naked warriors and nobles. A horse was in waiting to receive the princess, who was mounted behind one of the clerks, and thus conveyed, coy but compliant, to the fortress. Here she was received with devout, though decent joy, by her expecting bridegroom.

Her bridal adornments, it is true, at first caused some little dismay, having painted and anointed herself for the occasion according to the Chinook toilet; by dint, however, of copious ablutions, she was freed from all adventitious tint and fragrance, and entered into the nuptial state, the cleanest princess that had ever been known, of the somewhat unctuous tribe of the Chinooks.

From that time forward, Comcomly was a daily visitor at the fort, and was admitted into the most intimate councils of his son-in-law. He took an interest in everything that was going forward, but was particularly frequent in his visits to the blacksmith’s shop; tasking the labors of the artificer in iron for every state, insomuch that the necessary business of the factory was often postponed to attend to his requisitions. …”

Paul Kane wrote about Ilchee and Duncan McDougal in his Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, published in 1859:

“… [Ilchee] was the daughter of the great chief generally known as King Com’comly, so beautifully alluded to in Washington Irving’s “Astoria”. She was formerly the wife of a Mr. McDougall, who bought her from her father for, as it was supposed, the enormous price of ten articles of each description, guns, blankets, knives, hatchets, &c., then in Fort Astoria. Com’comly, however, acted with unexpected liberality on the occasion by carpeting her path from the canoe to the Fort with sea otter skins, at that time numerous and valuable, but now scarce, and presenting them as a dowry, in reality far exceeding in value the articles at which she had been estimated. On Mr. McDougall’s leaving the Indian country she became the wife of Casanov . . .” In 1813, when Astoria was turned over to the British, McDougal left. Ilchee eventually traveled up the Columbia to the Vancouver area and married Chief Casino (often seen as “Casanov”), a Chinook chief and successor to Chief Com’comly, before returning to her home at the mouth of the Columbia.

~~~

In 1823, in the ‘custom of the country,’ Archibald McDonald took a Native wife, Princess Raven – Koale’Koa – daughter of the influential Chinook chief Com’comly. Early in 1824 a son, Ranald, was born to them. Raven did not long survive the baby’s arrival, and Ranald was sent to live with his mother’s sister, Ilchee, in Com’comly’s lodge.

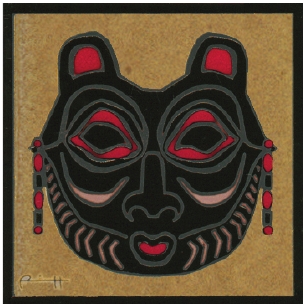

~~~ photo of Ilchee by Mas Yatabe

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on The Marriage of Ilchee and Duncan McDougal

June 26th, 2011

“Once there were a people so wealthy, plump, and sleek that they drank sea lion oil straight and didn’t have to look for food all winter long. They danced and sang and recited stories instead. These people’s upriver neighbors bent under ninety-pound packs. These people just carried their big boat down to their river, piled in several tons of trade goods ( cranberry preserves, smoked salmon, dried clams, six or seven kinds of vegetables, fur robes, and arrow-proof battle armor ) and paddled a hundred miles or so up the river to trade.

They were not just rich but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows. but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

What to call these people is a problem. The name Wimah merely meant “Big River,” which was the same meaning all of the other three languages above the Chin on the river called it. But the people had no name at all for themselves. Each village had a name, and there were names for groups of villages that spoke the same dialect, but each village was really separate, indeed each family was separate, though inextricably connected by relationships to other families. A man might take his house planks and dependents, and paddle up to the next village, and then he was one of those people. As for a name for all those who spoke Chinookan languages, fifty or more winter villages strung along both banks of the lowest two hundred miles of the Columbia River, plus twenty-five miles up the Willamette River at the falls and the Clackamas River, and twenty miles north and south along the Pacific seacoast, for all those people the river people had no name, indeed hardly more than a memory that they must be related.

When the first European ship sailed into the river and anchored eight miles above the mouth, offshore from proud Qwatsamts, a three-row village, the mariners wanted to know what to call the people. One sailor asked some sort of question, in some approximation of language, pointing at the village. Something like, “What are these people called?” (Pointing, by the way, was dangerous and ill-mannered among these people.) A headman or spokesman responded Chinoak or Tsinuk or something like that. Forever after, the white people called the people in that village, and three or four others along the riverbank nearby, Chinook or Chinooks. (The river people at first called the strangers tlohonnipts, “those who float [or drift] ashore.”)

After a while, when they learned that the people upriver for a couple of hundred miles had roughly the same languages, the tlohonnipts called them Chinook, too. Years later, all canoe-paddling Indians on the North Pacific Coast were sometimes referred to as Chinooks. All that, based on no more than what some person answered when strangers impolitely pointed toward the village of long cedar-plank houses, row on row along the shore, which town they called Qwatsamts.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed. Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

In trade they were very like us, but in other ways they were utterly opposite. Our Western heritage contemplates a universe where there is one central God and all the subordinate creatures take their identities in relation to that over powering One. The Chinook believed the world a multiverse where everything was alive and had its own spirit. The powers of the spirits differed widely but there was no central all-powerful One.

The Chinook lived along the river for thousands of years. Then pale strangers floated ashore, and within forty years the Chinook were pretty much gone. All but a few in the center of their land disappeared, a great majority of those at the seacoast and Willamette Falls, a relatively smaller percentage at the eastern edge, up the Columbia River Gorge. In much of that area their culture was shattered.

Tsagiglalal saw all this happen, from her rock at the uppermost end of the Chinook-occupied river. Tsagiglalal is a beautiful broad face, with luminous eyes and wide smile, her tongue thrust out, inscribed on rim-rock at the easternmost edge of the Chinook land. Coyote, their myth age trickster-hero, put her there to watch the people. “She Who Watches” they called her. She became a symbol of conscience and of death. “She sees you when you come,” they said, “she sees you when you go.”

What, if anything, did the long persistence and swift collapse of the Chinook mean? They were living so nicely. They had all they wanted and nobody to bother them, were wealthy and respected. Then, because of the skin of a sea mammal and a host of spirits too small to see, thousands of them died, their culture crumbled and the survivors were sent away in a cruel diaspora.

They didn’t sign away their rainy Eden or sell it, they didn’t die in warfare, or move to reservations, not until twenty-five years after the catastrophes that swept most of them away. It wasn’t smallpox that laid them low. Suddenly most them were simply gone. The Wapato Lowlands in particular were empty and silent. Did God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

This book is meant to remedy that lapse of memory. Naked Against The Rain, Far Shore Press, Portland, OR, 1999.

***

She Who Watches has also been called the stone Owl Woman who watches. Indian women have gone to the stone and knelt before it. They would say something like, “You who watch, please look into me and see my problem and help me to solve it.” A ray of light would come down to shine on the stone face then. After the woman goes to her teepee to sleep a dream would come telling her how to deal with the problem. Maybe that woman would go again to the stone and the ray of light would come down again on the stone, and the next dream would give even more detail as to how to solve the problem.

From: Tahmahnaw, The Bridge of the Gods, by Jim Attwell.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on She Who Watches — Tsagaglalal ~ By Rick Rubin © 2000

May 23rd, 2011

利尻島にも春が来ました。博物館前庭のチシマザクラが開花。でも、肌寒さは相変わらず。冷え込む利尻島の春です。

Spring has finally come to Rishiri-to. The Chishima Cherries have opened in the front garden of the Rishiri Museum, however, the air is cool – as usual. That’s a typical spring in Rishiri.

~photo by Eiji Nishiya

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Spring Has Finally Come to Rishiri-to

May 23rd, 2011

The annual membership luncheon of the Friends of MacDonald, chaired by Mas Yatabe, was held on May 14, 2011 at the Baked Alaska Restaurant in Astoria, OR. Notable people among the attendees were Consul General of Japan Takamichi Okabe and his wife, Kozue, Dr. Stephen Kohl, author and retired professor of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of Oregon and his wife, Katie, and representing the Chinook Nation, Councilman Charles Funk and his wife, Mary. Also in attendance were McAndrew “Mac” burns, Executive Director of Clatsop County Historical Society and his daughter.

The agenda included a State of the Organization and financial report presented by Chairman Mas Yatabe. Also discussed was a plan to distribute Unsung Hero, written by Atsumi McCauley and illustrated by Mariko King. Unsung Hero, a bilingual children’s book about the young adventurer, Ranald MacDonald, is written in both Japanese and English text with full-page, color illustrations. It is the intention of Friends of MacDonald to present gift copies to local Astoria elementary schools as well as to selected elementary schools in the greater Portland/Clark County area. Councilman Charlie Funk brought news that the Chinook Indian Nation, the State of Washington, and the National Park Service are working together to develop a new national park unit. This unit, named “Chinook Middle Village – Station Camp”, and authorized by Congress in 2004, will focus on the first 30 years of the relationship between the Chinook and the United States, a period of time that encompassed the Lewis and Clark Expedition as well as the founding of Astoria, and will most certainly focus on the life and times of Concomly, the principal chief of the Chinook Confederacy and grandfather of Ranald MacDonald.

This new national park unit will be directly adjacent to Fort Columbia State Park and is hoped to be open in 2011.

Alice Yatabe, who developed the website for Friends of MacDonald, discussed the organization’s original mission, reading from a letter written in April 1991 by Donald Sterling, FOM Charter Member, long-time journalist and past-President of the Oregon Historical Society. Yatabe quoted Sterling as calling Ranald MacDonald “the personification of the early contacts between the West and Japan in the mid-19th Century”, and encouraged the Friends to continue to assemble and disseminate information about a wide range of related subjects rather than concentrate only on MacDonald’s own life and adventures. Yatabe pointed out that FOM was currently doing this by re-connecting with the Chinook Nation as well as with Clan McDonald, both in the USA and Scotland – and by FOM’s on-going close relationship with Friends of MacDonald Japan.

As the informal luncheon came to a close those in attendance were treated to a beautiful solo rendition of Chidori No Kyoku performed by Mrs. Kozue Okabe on koto before everyone moved to the MacDonald Birthplace Monument on the corner of 15th and Exchange Streets, the site of the original Ft. Astoria, for a group photo.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on FOM Annual Membership Meeting May 2011

March 22nd, 2011

The Oregon Japan Relief Fund has been set up by the organizations listed below to provide financial aid to the Tohoku region in Japan in the wake of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. One hundred percent of your contributions will be contributed to Mercy Corps, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation based in old Japantown in Portland that has been helping to alleviate suffering across the globe for 32 years. We hope that you will contribute generously to help those suffering in Japan during this extremely difficult time.

日本で発生しました東北地方太平洋沖地震と津波のための緊急災害募金をオレゴン州でも日本救済支援基金して受け付けております。すべての寄付は全額 Mercy Corpsという団体に渡されます。この団体は32年もの間、ポートランドのジャパンタウンを拠点として救助を支援してきた団体です。この緊急の災害時に 皆様の寛大な寄付をどうぞよろしくお願い致します。

(Some browsers are unable to view the Japanese translation above)

Participating Organizations and Businesses:

Azumano Travel

Beaverton Sister Cities Program

Center for Japanese Studies at PSU

Ikebana International Portland Chapter #47

Japan-America Society of Oregon

Japan Exchange and Teaching Program Alumni Association of Portland (JETAA Portland)

Oregon Nikkei Endowment

Oyanokai

Portland JACL

Portland Japanese Garden

Portland Public Schools

Portland Rose Festival Foundation

Portland-Sapporo Sister City Association

Portland Taiko

Shokookai of Portland

Tokyo International University of America

Willamette University

Wilsonville Chamber of Commerce

For those of you wishing to make a contribution by check, please send your check to:

Mercy Corps

45 SW Ankeny Street

Portland, Oregon 97204

Note: Oregon Japan Relief Fund

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on “From Oregon With Love” . . .

February 28th, 2011

ゴマフアザラシ

海岸の岩場で日向ぼっこするゴマフアザラシ。

近づいて行くと

「どうしたの、何かあったの?」と、聞かれた。

「シバレルね」と応えると

「そんなことないよ」と言って、岩場を降りていった。

I spied a spotted seal “sunbathing” on the rocks.

As I approached he asked, “Can I help you?”

“It’s really cold, isn’t it?” asked I.

“Not for me,” he answered as he slid into the icy sea.

photo and 'poem' by Eiji Nishiya, FOM, Rishiri Island

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Seal on the Rocks

February 3rd, 2011

日の入り

二月三日は月暦正月朔。

一年の初めに紅く丸く、海に入る日の入り。

利尻山頂が紅く映えていた。

明日は立春。春の気立つ日。

今年は暖かく晴n日が続くのだろうか。

“The sun is entering the ocean.”

“The red and round sun goes in to the ocean for the last time this year” … Rishiri mountain in the alpenglow of sunset on the last day of the year [according to the old-style, Japanese lunar calendar.] Tomorrow, February 3rd, is “risshun” [considered the first day of spring in Japan]. The “sense” of spring begins. I wonder if we will be blessed with warm, sunny days? ~Eiji Nishiya

Today is also the eve of Ranald MacDonald’s (187th) birthday.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Last Rishiri Sunset of the (old) Year

January 17th, 2011

Winter surf on Rishiri-to. Looks pretty cold, doesn’t it? Photo courtesy of Eiji Nishiya, Curator Rishiri Museum

The latitude of Rishiri Island is 45.15 degrees north — Ft. Vancouver is 45.30 degrees north [a coincidence, certainly, but an interesting bit of trivia nonetheless]. Many thanks to Mr. Eiji Nishiya, curator of the Rishiri Museum and Secretary of FOM Japan – and most excellent photographer! – for his many contributions to our web pages.

オオワシを見た。

ここ数年渡来している場所。

高い所から何を見ているのだろうか。

I watched a giant white-tailed eagle return

to the same place she’s been coming in recent years …

I wonder what she’s looking at from that high perch?

~Eiji Nishiya

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Winter on Rishiri-to

January 17th, 2011

The next post will definitely take on an ‘academic’ tone, sort of like what you’d find on The History Channel, but I think it is important to be able to place oneself shoulder-to-shoulder with Ranald MacDonald before one can really appreciate what it was like to live as a Metis – a half-European, half-Native American — in 19th Century North America [and beyond].

Many of us at Friends of MacDonald are familiar with the biography of MacDonald and can recite a near-litany of his many accomplishments, most particularly those events leading up to and including his clandestine entry into Japan in July of 1848. Though celebrated among those of us who know about his history as a world traveller and quasi-diplomat, in regards to his DNA, Ranald MacDonald was in no way unique.

When celebrating the history of the Celtic peoples in the New World, one must include the descendants of their liaisons with the First Peoples, for here is where we find many of the greatest stories on this continent. The joining of these two tribal cultures resulted in some of the greatest warrior-heroes to walk the planet – just when their people needed them the most. The traditional powers of the Old World (Britain, Spain and France) were locked in mortal combat over the vast resources of the New World. These “resources” included the “Coilltich“, the Gaelic word for the “forest-folk” – the term the Highlanders had for the Red Man.(1)

From the Gaelic periodical, Cuairtear nan Gleann, 1840, translated:

“There is no People on the face of this earth who, in matters of war or hunting, can surpass the Indians who inhabit the region of America not inhabited by the white people. They are now (alas!) few in number compared to what they were at one time; for, as the white people become more numerous and powerful, the Indians are scourged backwards before them, from place to place; and are injured by every sort of the most merciless brutality and violence.”

“The American Indians are very refined in their language and they are eloquent and expressive in their manner of speaking.”

It is possible that the Gaels realized that Native Americans were the disposed and disenfranchised of America in the same sense that the Gaels themselves had become the subject race of Scotland, driven out of their home by Clearances that continued into the early twentieth century.(2)

It is no wonder then, that the Highlander would leave the English on the coast of America and settle on the frontiers of the 18th and 19th centuries, intermingling with the tribes and settling down with the women of the First Peoples. “Such unions enabled them to enjoy better relations with their wife’s tribe, gave them a partner with the knowledge and experience necessary to survive in the wild, and bestowed full “native status” to their children on account of the matrilineal reckoning of Native American society.” Those children, who, having the bloodlines of two warrior tribes from different ends of the planet, made their indelible mark on history for both the Coilltich and the Ceiltich.(3)

To better understand Ranald’s story – who he was as well as his place in the history of this continent (and even in world history) it is important to understand and become familiar with what “his” world was like. This article will be the first in a series of articles that will hopefully provide some meaningful background to help us all better empathize with the “Life and Times” of Ranald MacDonald.

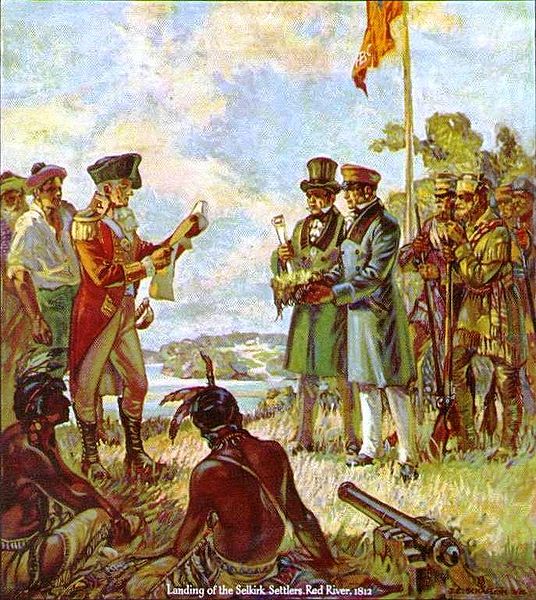

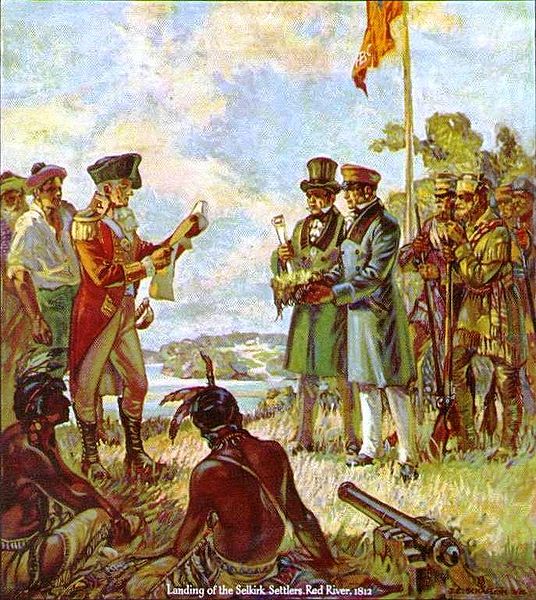

Landing of the Selkirk Settlers, Red River, 1812, J.E. Schaflein HBC’s 1924 calendar illustration, H.B.C. Archives

The fur trade – and the subsequent arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Company – had various effects on the northern First People [indigenous] populations from the Oregon Territory on the Pacific coast to the northwestern portion of the Northwest Territories and across South and Central Canada. The fur trade itself had already disrupted previous economic relationships between indigenous groups, and in some examples the presence of the Hudson’s Bay Company furthered tension between these groups as each vied for the control of fur-rich regions and sole access to specific Company posts. Though the Tribes may have competed with each other, due to the frontier nature of the region, the relations between fur trade companies and First Peoples was, by necessity, generally one of mutual accommodation. [This was in stark contrast to other European-First People relations.] The fur trade was dependent on indigenous trappers. This dependence resulted in a certain amount of respect for the ability of the indigenous trappers to locate fur-rich areas. Merchant firms such as the Hudson’s Bay Company were subject to market competition, and this in itself encouraged “fair behavior”. Another factor was that the White Traders and the First Peoples were too dependent upon each other to allow any type of extensive exploitation to occur.

The first large wave of Scottish immigration to Canada occurred between 1770 and 1815, when some 15,000 individuals moved to places like the Selkirk Settlement in current-day Manitoba, as well as to settlements along the East Coast and eastern Ontario. A significant number during the fur trade were men, and many of them would settle with Aboriginal women to create the Métis. During the great wave of immigration to Canada’s West during the 1800s and early 1900s, the Highlanders were the preferred group of immigrants because of their hardiness and their adaptability to farming, and these men were highly sought after. Archibald McDonald, Ranald’s father, was just such a man.

Winter Sunlight on Glencoe and Loch Leven ~ Copyright Jim Stewart

Archibald McDonald was born at Leeckhentium, on the southern shore of Loch Leven, Glencoe, Appin, in North Argyleshire, Scotland, on February 3rd, 1790. [His paternal grandfather, Iain (or John) McDonald, had been one of the few male survivors of the Massacre of Glencoe** in 1692.] It is said that Archibald was well educated and studied the rudiments of medicine at the University of Edinburgh before immigrating to Canada as a member of Lord Selkirk’s Colony(4) at Red River (Manitoba) in 1813, where he assumed a considerable share in the management of the Colony’s affairs, in part because he could act as an interpreter between the overseers of the colony, who spoke English, and the settlers, who, like him, were native Gaelic-speakers. [Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771~ April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk and was part-owner of the Hudson Bay Company.]

After Lord Selkirk’s death in 1820, his executors administered the colony, and sought to reduce expenses by ending settlers’ subsidies and refusing to recruit new European immigrants. Consequently, population growth came largely through the retirement of fur traders and their native families to the colony, encouraged by the newly-formed Hudson’s Bay Company’s reduction of the number of its employees. In the spring of 1820 Archibald entered the service of the H.B.C., shortly after the union of the H.B.C. and the North West Company; in 1821 H.B.C. Governor George Simpson sent McDonald to the Columbia district, on the Pacific Northwest coast, where he first served as accountant at Fort George [Fort Astoria].

It was at Fort Astoria in 1823 that Archibald was married “according to the custom of the country”, to the princess Koale’zoa (also known as Raven or Sunday) (d. 1824), daughter of Chinook chief Comcomly, with whom he had one son, Ranald McDonald; Archibald married a second time in 1825, also according to the custom of the country, Jane Klyne, a Metis [mixed-blood] woman with whom he had twelve sons and one daughter.(5)

McDonald was one very busy man; we might even be tempted to call him an ‘over-achiever’. At the very least his resume` is impressive. The following information is taken from Archibald McDonald: Biography and Genealogy, an article written by William S. Lewis and published in the Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 1918 : “In 1824 Archibald McDonald was one of the clerks in charge of posts in the Thompson’s River District, also known as the Columbia District. He succeeded John McLeod, Chief Trader, at Kamloops in the Thompson’s River District, in 1826.(6) In July 1828 he accompanied Governor George Simpson of the H.B.C. on a canoe voyage from York Factory, Hudson’s Bay to Fort Langley, New Caledonia, where he succeeded James McMillan.(7) He remained at Fort Langley until the spring of 1833. While stationed there he inaugurated the business of salting and curing salmon for market. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 15, 1831, McDonald wrote: “Our salmon, for all the contempt entertained for everything outside of the routine of beaver at York Factory, is close up to 300 barrels.”(8)

In 1833 he suggested the idea of raising flocks and herds on the Pacific Coast.

McDonald left Fort Langley for Fort Vancouver and on May 1833 selected the site and helped lay the foundation of Nisqually House [near present-day Tacoma, WA.] In July of that year he accompanied William Connolly up the Columbia with supplies for the interior, for the purpose of proceeding overland to enjoy a furlough. He spent 1834-35 in Scotland. Returning in the spring of 1835, he took charge of Fort Colville in 1836.(9) McDonald was stationed at Fort Colville from 1836 to 1843. In 1842 he was promoted to Chief Factor. While in the Columbia River district, Archibald had charge of and was eminently successful in placing the land in cultivation, and acquiring and raising horses, cattle, sheep, etc. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 25, 1837, McDonald states, “Your three calves are up to 55 and your 3 grunters would have swarmed the country if we did not make it a point to keep them down to 150.”(10)

Writing in September, 1837, Rev. Elkanah Walker thus describes Archibald McDonald’s farming operations at Fort Colville:

“It was truly pleasing after being nearly half a year without seeing anything that will bear to be compared with good farming, to see fenced fields, houses and barns grouped together, with large and numerous stacks and grain, with cattle and swine feeding on the plain in large number. There is more the appearance of civilized life at Fort Colville than any place I have seen since I left the States, and more than you see in some of the new places in the States … Mr. McDonald raises great crops. He estimates his wheat this year at 1500 bushels and his potatoes at 7000 bushels. Corn is in small quantity in comparison with his other grains.”

While at Fort Colville, in the early forties, Archibald McDonald is said to have had many hundred acres under partial cultivation. His son, Benjamin, stated that his father had nearly five thousand acres of land under cultivation at one time in the vicinity of old Fort Colville. Mr. Jacob A. Meyers places the maximum of land in agricultural use by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the vicinity of Fort Colville at 2000 acres, including in this estimate hay lands some twelve miles distant in the neighborhood of the present town of Colville. The company also held six townships of pasture lands obtained from the Indians by treaty.(11) [In his later years, Archie’s son Ranald panned the creeks flowing into the Kettle River and Boundary Creek in search of gold; Ranald died on the Colville reservation in 1894 in the arms of his niece, Jenny Lynch, the daughter of his half-brother Benjamin.](12)

At Fort Colville, Archibald supervised the reconstruction of the old sawmill, said to have been originally built in 1826-9, and the first sawmill on the Pacific Coast north of California. The original roof boards of the old fort buildings, of mill-sawn lumber, and lumber for company boats, bateaux and other purposes came from this mill. McDonald also supervised the rebuilding of the gristmill on “Mill Creek” (now Meyers Falls of the Colville River).

During Archibald McDonald’s many years in the Northwest he made no less than 15 trips across the continent between 1812 and 1845. He also kept very accurate journals, describing the country as regards to topography, soil, timber, rivers, climate, etc., through plains and over mountains, from Hudson’s Bay and the Great Lakes to the Pacific.

On his retirement from the H.B.C. in 1844 he moved overland with his family to Montreal, where he resided for two years. He then moved to St. Andrews on the Ottawa River, where he purchased a large tract of land and established a permanent home. He called his residence “Glencoe Cottage” and here he continued to live until his death on January 15, 1853, at the age of 62 years. Sadly, he may have died believing that his eldest son Ranald had perished at sea, though according to Fred Schodt in Native American in the Land of the Shogun, “ … this was unlikely. On April 3, 1852, the month before he removed Ranald from his will, Archibald wrote to a relative in Ft. Colville: ‘From Ranald, the Hero of Japan, I had several letters since his withdrawal from Jedo (sic) – He sticks to the sea, and last sailed from London for Sidney. But I trust now he will prefer digging for gold in Australia to the precarious and uncertain life of a sailor.’ ”

In the business of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archibald displayed great initiative and energy, and, possessing also considerable executive and business ability, he was unquestionably one of the most capable chief traders in the Columbia River District. Moreover, Archibald McDonald was a likeable character. He was naturally of a kindly nature, and a most agreeable companion. During his many years in the Northwest he maintained an extensive correspondence with his contemporaries in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service. To visitors at his post he was a most courteous host. John McLean, writing in April, 1887, says, “We met with a most friendly reception from a warm hearted Gael, Mr. McDonald.”(13) Reverend Elkanah Walker, in his Journal, under date of September 17, 1888, writes of his arrival at Fort Colville, “Received a cordial welcome from Mr. McDonald and lady.” Subsequent pages of the Journal record many courtesies and kindnesses of the Hudson’s Bay Chief Trader.(14)

His family relations were ideal, and he at all times displayed a patient and earnest regard for the spiritual and temporal welfare of his children, to all of whom he gave such educational advantages as his means and the times permitted. “It is high time,” he writes, “for me to see and get my little boys to school – God bless them – I have no less than five of them all in a promising way.”(15) A highlander born and bred, Archibald McDonald was in the best sense of the term “a gentleman of the old school,” a man utterly fearless, and of greatest personal integrity and honor. McLeod in his Peace River (pp. 117, 91) describes him as “a gentleman of utmost suavity of spirit as well as form.”

“As the twig is bent, so grows the tree.” It seems that in this, Ranald MacDonald had a superior role model in the form of his father.

To be continued … ~A.M.Y.~~~

(1)The Legacy of Scottish Highlanders in the United States ~Michael Newton 2001 (2)Ibid. [3]Mike Dunlap, from the upcoming book, “New World Celts: Voyage to America”[4]Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771 — April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk[5]Jean Murray Cole, Dictionary of Canadian History On Line[6]McLeod’s Peace River[7]See Archibald McDonald’s Journal; McLeod’s Peace River[8]Washington Historical Quarterly, i, 265, July, 1907.[9]Washington Historical Quarterly/, ii, 254, April, 1908;[10]Ibid [11]Lieutenant Johnson gives the cultivated land in the immediate vicinity of the fort (1841) as but 130 acres. U. B. Exploring Exp., iv, 443.[12]Washington State History, Native Americans in Ferry County[13]John McLean, Notes of a Twenty-Five Years’ Service in the Hudson’s Bay Territory [14]Reports of the U. S. (Wilkes Expedition (1841), IV, 443, 454[15]Washington Historical Quarterly, ii, 163, January, 1908

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Ranald MacDonald’s World – Roots – Archibald and the H.B.C. Fur Trade

November 1st, 2010

文・写真:谷口雅春 / 2010年11月1日

なんと途方もない聞き書き本が僕たちにもたらされたことだろう。

前稿で露口啓二が紹介したように、このたび利尻町立博物館学芸課長の西谷榮治さんが著した「利尻の語り」は、1986年から23年もの長きにわたって北海 道利尻町の広報誌「広報りしり」に連載されてきた、島民やゆかりの人々の聞き書きを再編集したもの。B5版464ページの大部に、146人の語りと、内容 にちなむ写真がおさめられている(編集者西村淑子さんの丹念な仕事が偲ばれる)。

例えば伊勢から渡った海女たちの暮らし。ニシンの爆発的な大漁や、クジラが浜に寄り付 いた挿話。樺太との深い関わり。集落ごとの祭りや演芸会、相撲大会に血肉を踊らせた青年団の活動。盆や節句、あるいは学び舎の行事の数々。各地からの開拓 移住のあらましに、襞のように入り組んだ地名や地誌の言い伝え…。明治、大正、昭和にまたがるおびただしい主題が、欄外の注釈が欠かせないような独特の言 い回しで展開されていく。話し言葉をていねいになぞる筆致も魅力だ。

利尻に本格的に和人が移り住んだのは安政年間(1854〜1860)のことだという。 その前史として17世紀後半にはすでに松前藩の場所経営があり、時代を下れば今号のカイでもふれた、津軽や秋田藩士たちによるロシアへの備えがあった。北 海道本島と共通する水産資源と地政学的意味によって、利尻島の近代は急駆動される。内地とは比較にならない厳しく複雑な気候をまとった利尻山 (1721m)が海底から一気にそびえ、ごく限られた土地と海で繰り広げられてきた濃密な歴史は、この島の輪郭に北海道史の縮図や、「もしも世界が100 人の村だったら」といった思考モデルを誘うかもしれない。しかしそんな紋切り型のまなざしは、語りのディテールの強度の前に恥じ入るばかりだろう。本書に 満ちているのは、郷愁の下味がついた北方イメージの断片などではなく、記(しる)されることもなくひっそりと記憶に眠っていた、ひとりひとりの固有の身体 から編み上げた利尻島の風土であり、なまなましい人生そのものなのだ。

カイにも、まだ9回にすぎないが井上由美が連載している聞き書きシリーズ、「北海道の 物語」がある。聞き書きにおいて話し言葉から書き言葉への変換は、書き手をつねに正解のない問題の前に立ち止まらせる。本書からもその困難との折り合いの 軌跡が浮かび上がるが、464ページというボリュームは、口語と記述をめぐる日本語の成り立ちまでも意識させるだろう。読み進みながら想起したのは、水村 美苗の「日本語が亡びるとき」(筑摩書房.2008)だ。水村は、19世紀に「西洋の衝撃」を受けた日本の知識層が、その現実を語るために日本語の古層を 掘り返し、日本語のあらゆる可能性をさぐりながら「出版語」を作りだしたこと(その言葉によって日本の近代文学は立ち上がった)。言文一致とは、単に口語 を書き言葉に移した取り組みではなく、幕末から明治の東アジアの激動の中で考案され磨かれてきた壮大なプロジェクトだったこと。そうした史実に無頓着なま ま、緊張感をなくした日本語はインターネットの時代に英語に飲み込まれようとしていることをスリリングに論考する。同次元で「利尻の語り」には、亡びゆく 土地の記憶をなんとかつなぎ止めようとする、現代日本語の格闘が浮かび上がっているともいえる。

マネーやイメージは根を持たないが、人間は土地を離れて生きることができない。20年 以上の歳月をかけ、これからもなお続く聞き書きは、利尻で生まれ育ち東京で学び、利尻に根ざし続けることを選んだ西谷さんにしかできない仕事だろう。受け 止める僕たちは、亡びるものへの感傷などで視界を汚してしまう前に、語りのリアルな細部から、北海道がほんとうに守るべきものや受け継ぐべき価値をしっか りとまさぐっていきたい。

(自費出版。3,360円で実費発売。問い合わせは利尻町立博物館 tel:0163・85・1411へ)

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on 西谷榮治 『利尻の語り』 を読む

|

|

|

but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows. Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.