|

April 10th, 2012

Photo by Mas Yatabe, taken at Portland Japanese Garden

Article By Ichiro Fujisaki, Ambassador of Japan to the United States ~ Reprinted from The Washington Post, January 21, 2012

This spring will mark the 100th anniversary of the chilly day in late March 1912 when two women in heavy coats dug into the earth along the north edge of the Tidal Basin to plant saplings. First lady Helen Taft and Viscountess Iwa Chinda, the wife of the Japanese ambassador to the United States, were joined by just a few people as they helped cherry blossom trees from half a world away take root in the nation’s capital.

When William Howard Taft became president in 1909, neither the Jefferson Memorial nor the Lincoln Memorial had been constructed. Mrs. Taft was hoping to host outdoor concerts and felt that the Tidal Basin area needed some embellishments.

Eliza Scidmore had long awaited such an opportunity. Scidmore, a travel writer, had fallen in love with the cherry blossom trees she saw gracing river banks in Tokyo while she visited her brother, a U.S. diplomat, when he lived in Japan. She had been trying for two decades to persuade authorities to plant them in the District.

David Fairchild of the Agriculture Department shared her view. Before the first lady’s project arose, he had imported some seedlings from Japan and given them to D.C. schools. Scidmore and Fairchild thought that the first lady’s project was a golden opportunity and recommended planting Japanese cherry trees. Mrs. Taft, who was familiar with cherry blossoms from visits to Japan, liked the idea and immediately requested the trees be planted. Col. Spencer Cosby was given the task.

At that time, renowned Japanese chemist Jokichi Takamine, who lived in New York, was visiting Washington. He was an advocate of improving U.S.- Japanese relations and was concerned by the hardening atmosphere in the United States toward Japan. Believing that the cherry blossoms could be a bridge between two peoples, Takamine had been working for years to persuade New York authorities to plant cherry trees along the Hudson River.

Takamine heard from his friend Scidmore about the first lady’s idea, and he proposed to donate 2,000 trees from Japan to the project. The Japanese consul general in New York, Kokichi Mizuno, who was also visiting Washington and was at the meeting with Takamine and Scidmore, proposed making the trees an official gift from the mayor of Tokyo, Japan’s capital city. Takamine, as a leader of the Japanese community in New York, agreed, and he went so far as to suggest to other Japanese in New York that, if official funding was not possible, contributions should be made by the leaders themselves.

The first lady welcomed the Japanese initiative. While Mizuno was communicating this situation to headquarters, the Japanese ambassador to the United States, Kogoro Takahira, confirmed the plan with the U.S. Secretary of State and also recommended to Japan’s foreign minister that the trees be an official gift from Tokyo. The Foreign Ministry then formally contacted the city of Tokyo. Mayor Yukio Ozaki, who was thankful for the role the United States had taken preparing negotiations leading to the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the Russo-Japanese War, seized this opportunity.

In 1909, he acquired the Tokyo City Council’s consent to donate 2,000 saplings. Transport across the Pacific was made available by Nippon Yusen Line, free of charge. Young trees about 10 feet tall arrived in Washington in January 1910. People were jubilant. The endeavor attracted media attention, including an article by Scidmore in Century magazine about the beauty of the trees. But just as it seemed everything had come together, U.S. Agriculture Department inspectors found that many of the trees were riddled with insects. The trees had to be burned. Ambassador Yasuya Uchida, who was then in Takahira’s post, wrote to Tokyo to defend the measures U.S. officials had taken and strongly recommended another attempt. The city of Tokyo decided, in April 1910, to donate as many as 3,000 specially grown germless saplings. This time the city took charge of the shipping as well. When the four-foot-tall saplings arrived in the District in March 1912, a thorough inspection was conducted. The trees were found to be in excellent condition, free from insects and plant diseases. It was decided that they should be planted at once. Only a few people, including Scidmore and Cosby, were present at the ceremony.

Ozaki visited Washington twice during the spring season. On both occasions, he composed traditional Japanese verses describing his strong attachment to those cherry trees Tokyo had given. His second visit came just five years after World War II, but he was honored in Congress for the gift. One of his poems reads:

“Viewing the cherry blossoms by the Potomac

Enchanted by the moon and appreciating the snow

There I will find the end of my life.”

Today, more than 3,000 trees surround the Tidal Basin, and approximately 100 of them are originals from 1912. When the Cherry Blossom Festival started in 1927, Mrs. Taft was the main guest, along with former first lady Edith Wilson. Just as the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France, has become a symbol of New York, cherry blossoms from Japan have become a symbol of Washington. The trees and their story are a living testament to the friendship between our peoples.

Commemorative Cherry Tree Planting at the Portland Japanese Garden ~

Thursday, April 12 ~ 10 a.m.–noon

Free with admission

In conjunction with the Japan-U.S. Cherry Blossom Festival Centennial and in collaboration with the the Consulate-General of Japan in Portland, the Japanese Garden will present a commemorative cherry tree planting in front of the Heavenly Falls on April 12th, 2012.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Cherry Blossoms and Friendship

February 4th, 2012

RISHIRI: A Pilgrimage … I want to say right now that I love Rishiri Island. A few FOM members have already written about their visits to various ‘Ranald-related places’ in Japan, and I was thrilled that, late in 2011, I got to go, too. This was a trip nearly two years in the making in part because of the sheer number of people and places we wanted to see while in Japan, but thankfully everything came together more or less as planned, and in late October we arrived at Wakkanai on the north-western tip of Hokkaido where we were met by our friend and long-time FOM member, Yamazaki-san, who, though he lives in Ebetsu, a suburb of Sapporo and a good 6-hour drive from Wakkanai, insisted on driving up to join us on the first leg of our journey – a two-day stay on Rishiri Island. It was our intent to spend time exploring Rishiri Island before catching the ferry back to Wakkanai and returning to Sapporo via Yamazaki-san’s car. [More about this later…]

Our passage from Hokkaido to Rishiri was uneventful – just the way most people like their ocean travel to be. The Sea of Japan was calm as we stood out on the narrow, windy deck and watched the silhouette of Rishiri-Fuji grow larger and more detailed as we approached, commenting to each other that this was the same mountain peak Ranald set his sights upon as he struggled to maneuver his small, unwieldy boat closer to land on that long-ago July morning. There are, in fact, real similarities between the appearance of Rishiri-Fuji and Mt. Hood – the mountain of Ranald’s childhood – although whether this had any effect on Ranald [e.g., did he also see the resemblance between the two peaks?] only he himself could say. In my own humble opinion, by the time he got close enough to Rishiri Island to make out the details, I would venture that Ranald really didn’t care what Mt. Rishiri looked like – he simply wanted to find a place to safely “castaway”.

Mr. Eiji Nishiya, the dedicated and enthusiastic curator of the Rishiri Town Museum, met us when we docked – camera in hand, of course. [We know many good photographers, but I have to say that Mr. Nishiya takes his photography seriously, and I am always excited to open his newest emails to see what treasures he has sent us.] Mr. Nishiya took us on a brief drive along the ocean before delivering us to our initial destination – a modest western-style, “beachside” hotel that served breakfast and dinner and had its own in-house ‘onsen’. I’ve put the word “beachside” in quotation marks because, as far as I saw, there are no beaches on Rishiri Island, at least not the sandy kind; in fact, the shoreline reminded me very much of the Oregon Coast between the Sea Lion Caves and Seal Rock, where barely-eroded basalt flows meet the Pacific Ocean. Consequently, Rishiri felt very much like home to me [I grew up on the Oregon coast] and I spent much of the following days trying to convince Mr. Y. that it might be nice to immigrate to Rishiri sometime in the future. Even the storm that moved in overnight could not change my mind . . .

We were awakened the next morning by the sound of wind and rain against our window, but we are Oregonians and a little wind and rain is nothing to us. Mr. Nishiya was ready for us and by mid-morning we were happily rummaging through the Ranald MacDonald exhibit at the Rishiri Town Museum. All three of us were impressed by the number and quality of the exhibits, ranging from artifacts of the Ainu First Peoples to the subsequent influence of the Japanese who eventually displaced them, a creditable natural history exhibit of common and indigenous flora and [stuffed] fauna, a section devoted to the local industry of fishing and sea-farming and – of course – a well-placed and very well organized area devoted to none other than Ranald MacDonald. We could have easily and quite happily spent a few days examining Mr. Nishiya’s own private stash of MacDonald treasures, but arrangements had been made for Mr. Nishiya and Mr. Yatabe to give a brief presentation about Friends of MacDonald to the student body of one of the two island junior high schools – and we were all pleased and gratified that, once they had heard the incredible true story of Ranald MacDonald the First English Teacher in Japan, the kids were genuinely interested in and enthusiastic about “their” local hero.

Next we loaded into Mr. Nishiya’s car and drove around the whole, rocky island. Except for the difference in temperature [and the lack of palm trees!] I could have almost imagined myself on Maui, again because of the abundance of basalt and ancient lava flows. In fact, more than a few of the rocks had names – “Neguma no Iwa” [Sleeping Bear Rock] and “Jimmen Iwa” [The Rock Face] are just two examples. Mt. Rishiri is extinct – its last eruption is estimated to have been in 5830 BC – give or take 300 years – and erosion has produced an extremely rugged topography, but the wind and the waves have not yet been able to break all that basalt down into sand. This includes Notsuka Cove, where it is believed that Ranald first set foot on Rishiri; marginally protected from the elements, it is still used today by local fishermen. Like every other Pilgrim to that place, we stood and gazed out over the Sea of Japan and tried to imagine how it had been for him. And then, again like the others before me, I bent down to pick up a rock – to bring back to Toroda as an offering, perhaps? I found several, and even pocketed a couple, but something made me keep looking. I was soon rewarded by a flash of turquoise between the wet stones – a piece of glass float, broken and tumbled by the waves. Of course, Ranald never saw any glass floats while he was in Japan – Japan didn’t start using the glass floats until 1910.

Before visiting Notsuka Cove we went to see the monuments memorializing Ranald’s exploits. The first has Ranald’s likeness and calligraphy of an excerpt from the novel “Umi no Sairei (海の祭礼)” (pub. 1986) by Akira Yoshimura (吉村 昭). The book became a sensation in Japan. There has been some confusion about the larger of the two monuments: in photos it looks as though there are two separate stones, but it is an illusion created by the way the granite is polished. This is, in fact, a single monument. The second monument on the left in the photo has the following inscription by Professor Emeritus of University of Hokkaido, Jyukichi Suzuki (鈴木重吉名誉教授) [Prof. Suzuki was born on Rishiri Island]:

“In 1848 ‘Kaei 1’ Ranald MacDonald born in Oregon reached ‘Notsuka’ pretending to be a shipwrecked sailar (sic). He felt deep racial connections with Japan across the Pacific although he knew of her total seclusion from the outside world. Inevitable he was arrested and sent to Nagasaki via Soya and Matsumae. During his imprisonment in Japan he did his best for mutual understanding and friendship between the two peoples transcending the language barrier. Five years later when Comm. Perry came to force open the closed doors of Japan, MacDonald’s former students at Nagasaki Einosuke Moriyama and others played an important role as interpreters. Thus Ranald enjoys the honor of being the first formal teacher of English and indirectly a father of modernizing Japan.”

Later that evening we were treated to a very private practice session of a Kirin Shishi-Mai (麒麟獅子舞) conducted by some local residents, including Mr. Nishiya – who plays the Japanese bamboo flute. During a short break in the practice one of the men looked at us and grinned broadly. “No ferry tomorrow, too stormy!” he said with a laugh. “100% no ferry!” We all looked at each other in disbelief – would they actually cancel the only ferry back to Wakkanai? We had a plane to catch in Sapporo, and a tight itinerary to follow! Luckily we managed to get the last two seats in the very rear of the daily prop-jet flight from Rishiri Island to Sapporo [which, we later found out, is also frequently cancelled due to weather]. Sadly, we had to leave Mr. Yamazaki behind, promising that we would indeed drive down the western coast of Hokkaido with him on another day. . . Later that evening we were treated to a very private practice session of a Kirin Shishi-Mai (麒麟獅子舞) conducted by some local residents, including Mr. Nishiya – who plays the Japanese bamboo flute. During a short break in the practice one of the men looked at us and grinned broadly. “No ferry tomorrow, too stormy!” he said with a laugh. “100% no ferry!” We all looked at each other in disbelief – would they actually cancel the only ferry back to Wakkanai? We had a plane to catch in Sapporo, and a tight itinerary to follow! Luckily we managed to get the last two seats in the very rear of the daily prop-jet flight from Rishiri Island to Sapporo [which, we later found out, is also frequently cancelled due to weather]. Sadly, we had to leave Mr. Yamazaki behind, promising that we would indeed drive down the western coast of Hokkaido with him on another day. . .

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on A pilgrimage …

January 31st, 2012

The last day of December 2011 – the day before the New Year of 2012 – the north wind blew off the cloud-cover over Mt. Rishiri and her rugged, snow-covered peaks appeared. The people of Rishiri turned toward our beloved mountain and gave thanks for another year of vigor and vitality.

辛卯・平成23年の大晦日. 利尻山にかかっていた雲を飛ばして秀麗の姿をあらわした。たくさんの元気をくれた利尻山に感謝.

“Farming” konbu in the middle of winter on Rishiri.

Konbu can grow 3-10 meters long in two years on the coasts of Rishiri Island; it is harvested and sun dried before being shipped. Only Konbu which has matured for two years is used for cooking [one-year-old konbu, called ‘water konbu’, does not contain the rich components needed for a good flavor]. Konbu has been a part of the Japanese diet since ancient times, and Rishiri konbu is considered by most Japanese people to be the “best”.

The winter winds blow from the northwest and bring snow to Rishiri. The north wind is called “ai” and the northwestern wind is called “tama“. When these winds blow, we on Rishiri Island exchange greetings: “”Shibareru ne?” – “It’s cold, isn’t it?” [A gross understatement, I think. ~A]

The cold is quite severe and penetrates through clothing to chill the skin. Still, it is necessary to remove the snow and ice from the boats, even on the coldest, most blustery days. There is never any rest for the fishermen of Rishiri.

北から北西の風が吹く利尻島. 北の風はアイ、北西の風はタマと言う。 この風が吹くと,「シバレルネ」が挨拶となる。 寒さが厳しく肌に凍みること。 吹雪いて船に積もった雪をとったり、時化で動かされる船を見たり,島人は真冬から船を守っている。

~ photos and comments by Eiji Nishiya

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Rishiri Winter 2012

October 13th, 2011

秋の森。

野の花たちや草が枯れる秋は森の中に入りやすくなる。

ツバメオモトの青い実をたくさんみつけた。

夕方、曇り空でもメヌショロ沼に利尻山が映った。

秋晴れの日。

利尻山頂がきれいに見えたこと。

岩場のウミウは陽射しで日向ぼっこしていた。

The forest in autumn …

It gets easier to walk into the forest when the flowers and the weeds have withered;

I found a lot of tsubame-omote there having blue fruit/seeds.

In the early evening, despite the cloudy sky, Mt. Rishiri reflected on Lake Nushoro.

Under the autumn sky the top of Mt. Rishiri could be clearly seen as the Sea- cormorants basked in the last rays of sun on the rocky shores.

tsubame-omoto [ ‘blue-fruit-plant’ ] – Japanese Wood Lily – Clintonia Udensis

photos by Eiji Nishiya

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Rishiri ~ Autumn 2011

September 15th, 2011

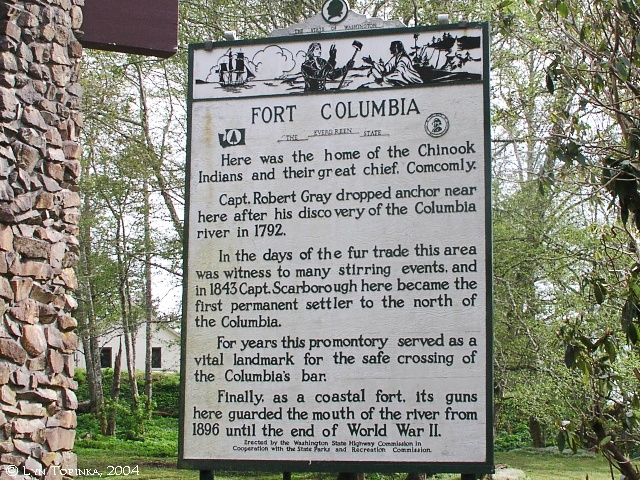

Clark’s Dismal Nitch

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson dispatched Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead the Corps of Discovery on a mission to find a water route across North America and explore the natural resources of the uncharted American West. Little did Lewis and Clark realize that the time they would spend on the shores of the lower Columbia River would be counted among the most discouraging, dangerous, and disagreeable experiences faced during their expedition.

Imagine this: it’s early 1805, the fresh food had run out. The clothes were literally rotting off the backs of the members of the Corps of Discovery. They were traveling as fast as they could down the Columbia River, hoping to meet one of the last trading ships of the season. If they made it, they’d send a set of journals and some collections home as requested by President Jefferson. But foremost was the chance to use an unlimited letter of credit from the president, a chance to “charge” all the goods the tired explorers needed [plus perhaps get a little rum] from the trade ship.

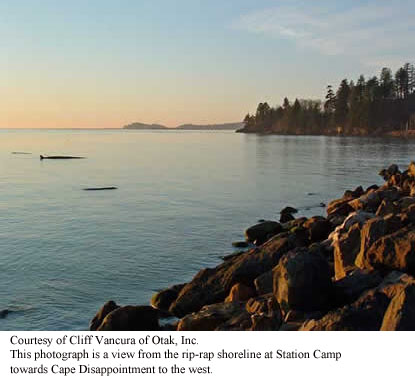

What the Corps didn’t realize, however, was that it was about to run into some of the journey’s most treacherous moments. A fierce winter storm forced the Corps off the river and pinned the group to a north shore cove consisting of little more than jagged rocks and steep hillside. On November 10th, as the party paddled past Grays Point, they saw that the steep, forested shoreline consisted of a series of coves, or “nitches”, each divided from the next by a small point of land. They passed present-day Dismal Nitch (also known as Megler Cove), but as the weather again worsened, the party retreated to a sheltered cove upriver from the Dismal Nitch, [approximately 600 feet north / northeast of the eastern end of the present-day “Dismal Nitch Safety Rest Area”].

Rain soaked the expedition party that night, and it continued at intervals throughout the next day, November 11, 1805. Conditions worsened on November 12th; on top of rain, wind and cold came thunder, lightning and hail. Clark describes their move from the unnamed cove to the Dismal Nitch:

“As our situation became Seriously dangerous, we took the advantage of a low tide & moved our Camp around a point a Short distance to a Small wet bottom at the mouth of a Small Creek (Megler Creek), which we had observed when we first came to this cove…”

The rain continued on November 13 and 14. For only the second time in the expedition, Clark said he was concerned for the safety of the Corps. “A feeling person would be distressed by our situation,” he wrote in wet misery, as the expedition became in danger of foundering just within a few miles of its destination – the Pacific Ocean. Finally, the storm broke and allowed the group to move on. It missed the trading ship, but eventually achieved its exploration goals. On the morning of November 15 Clark awoke to calm weather for the first time in 10 days. Clark describes the party’s escape from what became known as “the Dismal Nitch”:

“About 3 oClock the wind lulled and the river became calm, I had the canoes loaded in great haste and Set Out, from this dismal nitich where we have been confined for 6 days…”

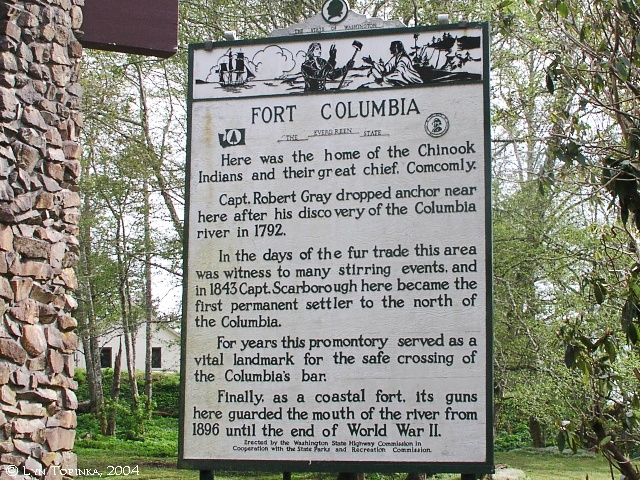

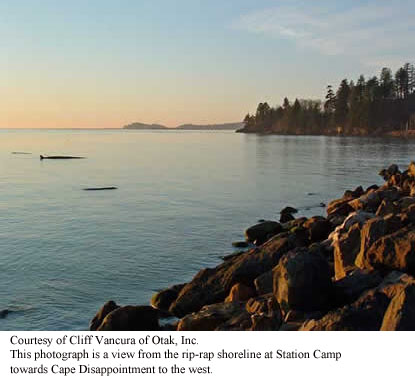

Although the Corps met “near disaster” at Dismal Nitch, they arrived “in full view of the ocian” at Station Camp. [It was at Station Camp that the famous vote was taken that included all members of the party and the party decided to move the south shore of the Columbia River where they would spend the winter before beginning their long journey home: more about this later.] However, both before and after Captains Lewis and Clark established Station Camp, the site was a vital and thriving Chinook Indian village. The Corps spent just 10 days here, but used Station Camp as a departure point for an overland trek to their first view of the Pacific Ocean and an exploration of the area. Together with nearby Dismal Nitch, Station Camp helps greatly to tell the Lewis and Clark story in Washington – and the ultimate effect the Corps of Discovery had upon the indigenous First peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

For thousands of years, the Chinook people have lived along the Columbia River and their home near the river’s mouth was strategically located to provide abundant food, such as salmon and shellfish. In addition, the nearby forests were home to game animals and the grasslands and marshes provided ample materials for making shelter, clothing and trade and household goods. The river provided a way for Chinook traders to travel to the south shore and up and down the Columbia.

Generations before the White Explorers came, the Chinook had already developed a sophisticated, rich culture and enjoyed great success as traders. The waterway near Station Camp became a virtual trade “water highway.” During the 10 years before Lewis and Clark arrived overland at this spot, almost 90 trade ships from Europe and New England are documented to have crossed the Columbia River Bar to trade with Native Americans. These ships brought metal tools, blankets, clothing, beads, liquor and weapons to trade for beaver and sea otter pelts. By the time the Corps reached the site, the Chinook’s had moved to their winter village and this village was unoccupied. The explorers spent almost two weeks there.

Several significant events took place, including the decision to spend the winter across the river, in what is now Oregon. It was Nov. 24, 1805, and the explorers desperately needed to lead the Corps to a winter campsite, one rich with game and near friendly tribes who would trade for supplies. A majority of the Corps, including the Indian woman Sacagawea and the African American York decided to cross the Columbia River to look for such a place. Because of this poll and decision, some historians call Station Camp “the Independence Hall of the American West.” It would be more than fifty years before African Americans could vote, and more than 100 years before the right was extended to women.

History of “Dismal Nitch”

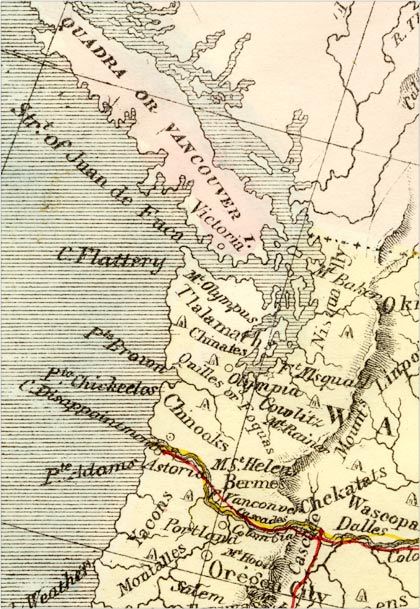

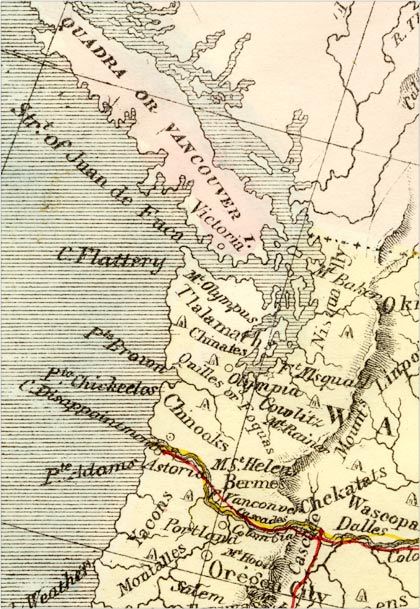

The Dismal Nitch area is located within the traditional territory of the lower Chinookan people. Through common usage, the term Chinook has come to refer to all speakers of the Chinook language family who inhabited the territory from the mouth of the Columbia River upstream to The Dalles and along the lower Willamette River to present-day Oregon City.

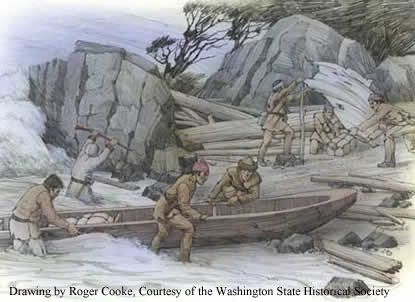

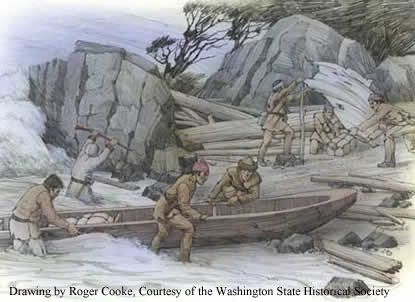

Of the many Chinook villages along the north shore of the Columbia River, two known summer villages were located in the vicinity of the Dismal Nitch. Approximately 1.25 miles southwest of the Dismal Nitch was Qaiitsiuk, later called Chinookville or Chenook, just west of present-day Point Ellice. The Lower Chinook were known for their canoe-building prowess, and their vessels helped them establish their reputation as traders well before Europeans set eyes on the region.

The Lower Chinook were first described in writing by Captain Robert Gray, who sailed into the mouth of the Columbia River in 1792, and by Captain George Vancouver, who also sailed into the area that year. By the time Lewis and Clark descended the river in the fall of 1805, the presence of Europeans on the lower Columbia River was not uncommon.

Today, the Chinook Indian Nation is made up of five separate tribes, including the Chinook, the Willapa, the Clatsop, The Kathlamets, and the Wahkiakum. All five tribes are Chinookan speakers.

The State of Washington is developing a park at Middle Village – Station Camp, focusing on the Chinook history, as well as telling the story of the Corps’. In 2005, archeologists found abundant physical evidence to support the importance of the site as a Chinook trade village. More than 10,000 artifacts were uncovered, including trade beads, plates, cups, musket balls, arrowheads, Indian fish net weights and ceremonial items. The European artifacts are from both before and after the Corps’ visit in 1805, and attest to the vitality of the Chinook social and economic life at the site. Station Camp eventually will encompass about 280 acres and be operated by the Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Station Camp http://www.nps.gov/lewi/planyourvisit/stationcamp.htm

History of "Dismal Nitch” http://www.nps.gov/lewi/planyourvisit/dismal.htm

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Station Camp and Clark’s Dismal Nitch

September 7th, 2011

紫陽花とコエゾゼミ

二十日盆のあと、お寺の境内でみられる紫陽花。

島人はいつもは秋が来るというが、

最近は残暑を感じさせるコエゾゼミの鳴きが響くようになってきた。

Ajisai [ hydrangea aspera ] [and ko-ezo semi [ terpnosia nigricosta ]

After the 20th day of O-bon we often see hydrangeas in the temple yard [compound]. Islanders say that autumn is coming. Lately, however, the sound of ko-ezo semi [cicada] makes us think that it is Indian Summer.

Photos by Eiji Nishiya, August 2011

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Indian Summer on Rishiri

July 27th, 2011

ハシブトガラス

めったに撮ることの出来ないハシブトガラス。

動きに敏感で、出来るだけ近づこうとしても、直ぐに飛んでしまう。

今回は珍しく、じっと動かないでいてくれた。

一羽でヤマグワの実などを食べていたので、私が離れるのを待っていたのだろうか。

愛嬌のある顔であると感じたが、敏感で人を襲うカラスとは思えなかった。

It is very unusual to see the HASHIBUTO GARASU [Corvus macrorhynchos]; she is very sensitive and cautious and flies away if you try to get close. This time, however, she stood still for my photo – which is a rare occurrence. Alone, she was eating the fruit of the YAMAGUWA tree, and paused, as if she were waiting for me to leave so she could continue with her feast. Her expression was so innocent and charming – it’s difficult to imagine that she will attack humans.

photo by Eiji Nishiya photo by Eiji Nishiya

The YAMAGUWA [Morus bombycis] or wild mountain mulberry has a prehistoric connection to humans. The use of mulberries has a long history in Japan, traceable to Jomon times. The fruit can be eaten or made into wine. The tree flowers in April to June with leaves; false fruits ripen from red to black in June to July. This mulberry is one of the most-common trees in Japan and is cultivated for feeding silkworms. The wood, hard and heavy, is used for furniture, cabinet work, inlaid works, and sculptures.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Summer on Rishiri Island

July 20th, 2011

Our people’s position at the mouth of the Columbia River and nearby Willapa Bay afforded us access to some of the richest arrays of resources on this continent. Waterways provided a network of trade routes that spread, like a spider web, hundreds of miles along the coast, and inland to Puget Sound, Hood Canal, the Chehalis River, and even onto the plains. The combination of these two factors culminated in a trading society unrivaled in the western half of the continent.

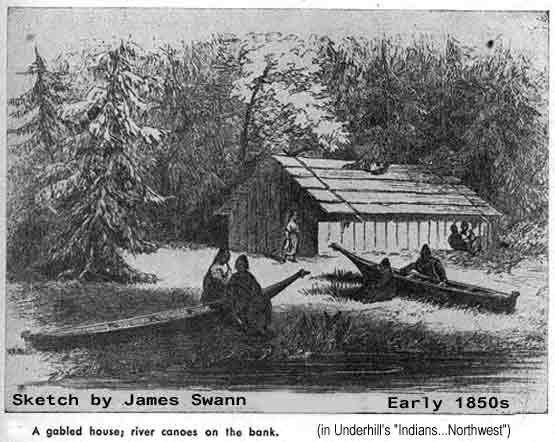

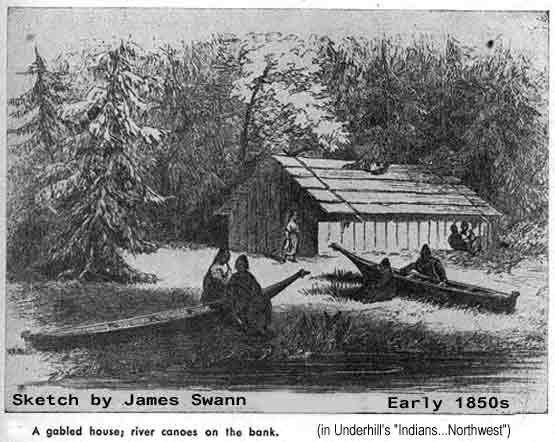

Semi-subterranean longhouses provided refuge from the endless rain and wind of winter, some large enough to house over a hundred people. Larger villages contained twenty or more longhouses of varying sizes. Inside these comfortable houses, the winter dances, songs and stories were told as the fires cracked and cast their long shadows. Some longhouses were temporarily abandoned for the summer fishing camps; others were occupied year round. the endless rain and wind of winter, some large enough to house over a hundred people. Larger villages contained twenty or more longhouses of varying sizes. Inside these comfortable houses, the winter dances, songs and stories were told as the fires cracked and cast their long shadows. Some longhouses were temporarily abandoned for the summer fishing camps; others were occupied year round.

Five types of salmon returned to the Columbia River and Willapa Bay in numbers unimaginable today. Indeed, they were the heaviest runs of salmon on earth. Smelt, sturgeon, suckers, several species of trout, whitefish, eels and other fish rounded out the wealth. The beaches offered an abundance of clams, mussels, oysters and the occasional stranded whale. Offshore were sea lions, harbor seals (olxayu), sea otters, and waterfowl by the millions. The forests were rich in elk, deer (Nawich), bear, beaver, river otter (nanANuks) and small game. Wapato (wapatu) abounded upriver, and the local plains turned purple with the flowering of the Camas (lakaNAs). Cattails, Rush, Sweet Grass Sedge, Nettle, Salmon Berry, Salal, Lilly bulbs and ferns were just a sprinkling of the plant resources. What was unavailable locally was obtained through our extensive trade network.

We were highly acclaimed canoeists, skillfully navigating the treacherous Columbia River and bar to the amazement of the traders and explorers. We plied the coastal waters from California to Alaska in canoes (kaniN) twenty-one to forty-two feet long and larger, carved from a single Red Cedar log and propelled by our distinctly notched, crescent-shaped paddles (isik) of Oregon Ash. It was this skill of travel, which transformed us into a tribe of tremendous wealth and power. We were highly acclaimed canoeists, skillfully navigating the treacherous Columbia River and bar to the amazement of the traders and explorers. We plied the coastal waters from California to Alaska in canoes (kaniN) twenty-one to forty-two feet long and larger, carved from a single Red Cedar log and propelled by our distinctly notched, crescent-shaped paddles (isik) of Oregon Ash. It was this skill of travel, which transformed us into a tribe of tremendous wealth and power.

Chinook life has always been dictated by a strict and complex system of taboos and ritual. Failure to follow ritual procedure might doom the individual, and/or the tribe, to bad luck, sickness or death. The rules and ritual formula could vary not only according to species, such as salmon, but might also vary according to location. For example, stranded whales (ikoli) are to be processed with extreme care, with strict accordance to guidelines, lest future whales drift away.

The myths and stories are steeped in the regiment of rules, and quintic references. The number five (qwinfN) is integral to Chinuk culture and appears repeatedly in the old stories and legends (ikanuN). From the five cold wind brothers, to the five salmon brothers, qwinfN is undoubtedly the most important Chinook number. The origins of its significance are obscure, although theories exist. One theory refers to the five directions. My personal, and totally unsubstantiated, theory is that it relates to the five salmon (qwAnat) species that run on the Columbia. Regardless of its origin, its power continues today. If you wish something to happen, repeat it five times. If you don’t want something to happen, well, repeating it five times would be a bad idea.

Trade goods were diverse, with slaves (ilaytix) and Dentalium (alIkHochick) being two of the most important items. Though most slaves were acquired through other tribes, the Chinook occasionally conducted slave raids of their own. Dentalium was the hard, claw-shaped shell harvested off the shores of Vancouver Island, usually by the Nootkan people. Dentalium was the money of its day, and many items were valued in comparison to fathom length strings (iLana) of the valuable shell. Other important trade items included powdered salmon from upriver, canoes, the double elk-skin clamons (armor), cakes of dried Salal berries, Mountain Goat horn and even dried Buffalo (duyha) from the plains. Obviously, with the exposure to such a diverse pool of skill and materials, the Chinook people were able to capitalize on a tremendous amount of knowledge and expertise.

[I consider cultural education to be of the utmost importance. Share what you learn with your children and relations. Learn the stories and songs, pass the legacy on, and the circle will continue. The rumors of our extinction have been greatly exaggerated. Hayu masi, “many thanks.”]

~~~ Greg Robinson, Volume I, 1st Edition

http://www.chinooknation.org

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Chinook Life Articles by Greg A. Robinson

June 26th, 2011

島に咲く花たち

いろんな花たちが咲き始めている。

島をまわる道路際には、シャク、エゾカンゾウ、チシマフウロがなど見られる。

のびてきている緑色の草の中に、群生している花たちを見つけて歩くことが楽しい。

海岸草原にはオレンジ色の花、エゾカンゾウが群生しています。

自然の花園の彩りは、いつも心を癒してくれます。

Pure white Wild Carrot (torilis japonicus) and bright orange Ezo-kanzou [Day Lily] grow in colonies in the meadows along the coast. The natural colors of the flowers always warm our hearts.

~~~ photos by Eiji Nishiya ~~~

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Early Summer on Rishirito

June 26th, 2011

To help us appreciate the First Peoples of the Columbia River Basin …

(Chinook, from Tsinúk, their Chehalis name). The best-known ‘tribe’ of the Chinookan family claimed the territory on the north side of the Columbia River from its mouth to Grays Bay, a distance of about 15 miles, and north along the seacoast as far as the north part of Shoal-water bay, where they were met by the Chehalis, a Salish tribe. The Chinook were first described by Lewis and Clark, who visited them in 1805, though they had been known to traders for at least 12 years previously(1) ~

“… This Chin nook Nation is about 400 Souls inhabid the Countrey on the Small rivrs which run into the bay below us and on the Ponds to the N W of us, live principally on fish and roots, they are well armed with fusees and Sometimes kill Elk Deer and fowl. our hunters killed to day 3 Deer, 4 brant and 2 Ducks, and inform me they Saw Some Elk Sign. I directed all the men who wished to See more of the main Ocian to prepare themselves to Set out with me early on tomorrow morning. The principal Chief of the Chinnooks & his familey came up to See us this evening …” [Clark, November 17, 1805] “… found maney of the Chin nooks with Capt. Lewis of whome there was 2 Cheifs Com com mo ly & Chil-lar-la-wil to whome we gave Medals and to one a flag. …” [ Wm. Clark, November 20, 1805 ]

Com’comly, grandfather of Ranald and the principle Chinook Chief of the time, received the Lewis and Clark expedition hospitably when it emerged at the mouth of Columbia River in 1805, and when, in 1810, the J.J. Astor Expedition arrived to take possession of the region for the United States, Com’comly cultivated a close friendship with the pioneers, even giving his daughter [Ilchee] as wife to Duncan McDougal, a Canadian fur trader who was at their head and who took part in the founding of Ft. Astoria in 1811.

Yet Com’comly may have been an accomplice in a plot to massacre the garrison and seize the stores. When a British ship arrived in 1812 to capture the fort at Astoria, Com’comly, with 800 warriors at his back, offered to fight the’ enemy’. The American agents, however, had already made a peaceful transfer by bargain and sale, and gifts and promises from the new owners [the North West Company] immediately made Com’comly their friend.(2) Writing in Aug., 1844, Father De Smet(3) states that in the days of his glory Com’comly, on his visits to Vancouver, would be preceded by 300 slaves, “and he used to carpet the ground that he had to traverse, from the main entrance of the fort to the governor’s door – several hundred feet – with beaver and otter skins.”(4)

The Chinookan nation was one of the most powerful native groups in Oregon. It included those tribes formerly living on the Columbia River, from The Dalles to its mouth (except a small strip occupied by the Athapascan Tlstskanai), and on the lower Willamette as far as the present site of Oregon City, Oregon. The family also extended a short distance along the coast on each side of the mouth of the Columbia, from Shoalwater bay on the North. to Tillamook Head on the South.

The region occupied by Chinookan tribes seems to have been well populated in early times. Lewis and Clark estimated the total number at somewhat more than 16,000. In 1829, however, there occurred an epidemic of unknown nature, which, in a single summer, destroyed four-fifths of the entire native population. Whole villages disappeared, and others were so reduced that they were, in some cases, absorbed into other villages. It can be assumed that it was the result of contact with a “white man’s” disease for which they had no immunity. The epidemic was most disastrous below the Cascades. In 1846 Hale estimated the number below the Cascades at 500, and between the Cascades and The Dalles at 800. By 1854 Gibbs gave the population of the former region as 120 and of the latter as 236. They were scattered along the river in several bands, all more or less mixed with neighboring stocks. In 1885 Powell estimated the total number at from 500-600, for the most part living on Warm Springs, Yakima, and Grande Ronde reservations in Oregon.

Most of the original Chinookan bands had no special tribal names, being designated simply as “those living at (place name)” This fact, especially after the epidemic of 1829, made it impossible to identify all the tribes and villages mentioned by early writers. Their language served as the basis for the Chinook Jargon which became the principal means of communication for the Indians from California to the Yukon, as well as trappers, traders and the majority of other individuals living and surviving in the territory.(5)

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Ranald MacDonald’s World – Chief Com’comly and the Tsinuk of the Lower Columbia

|

|

|

Later that evening we were treated to a very private practice session of a Kirin Shishi-Mai (麒麟獅子舞) conducted by some local residents, including Mr. Nishiya – who plays the Japanese bamboo flute. During a short break in the practice one of the men looked at us and grinned broadly. “No ferry tomorrow, too stormy!” he said with a laugh. “100% no ferry!” We all looked at each other in disbelief – would they actually cancel the only ferry back to Wakkanai? We had a plane to catch in Sapporo, and a tight itinerary to follow! Luckily we managed to get the last two seats in the very rear of the daily prop-jet flight from Rishiri Island to Sapporo [which, we later found out, is also frequently cancelled due to weather]. Sadly, we had to leave Mr. Yamazaki behind, promising that we would indeed drive down the western coast of Hokkaido with him on another day. . .

Later that evening we were treated to a very private practice session of a Kirin Shishi-Mai (麒麟獅子舞) conducted by some local residents, including Mr. Nishiya – who plays the Japanese bamboo flute. During a short break in the practice one of the men looked at us and grinned broadly. “No ferry tomorrow, too stormy!” he said with a laugh. “100% no ferry!” We all looked at each other in disbelief – would they actually cancel the only ferry back to Wakkanai? We had a plane to catch in Sapporo, and a tight itinerary to follow! Luckily we managed to get the last two seats in the very rear of the daily prop-jet flight from Rishiri Island to Sapporo [which, we later found out, is also frequently cancelled due to weather]. Sadly, we had to leave Mr. Yamazaki behind, promising that we would indeed drive down the western coast of Hokkaido with him on another day. . .

photo by Eiji Nishiya

photo by Eiji Nishiya

the endless rain and wind of winter, some large enough to house over a hundred people. Larger villages contained twenty or more longhouses of varying sizes. Inside these comfortable houses, the winter dances, songs and stories were told as the fires cracked and cast their long shadows. Some longhouses were temporarily abandoned for the summer fishing camps; others were occupied year round.

the endless rain and wind of winter, some large enough to house over a hundred people. Larger villages contained twenty or more longhouses of varying sizes. Inside these comfortable houses, the winter dances, songs and stories were told as the fires cracked and cast their long shadows. Some longhouses were temporarily abandoned for the summer fishing camps; others were occupied year round. We were highly acclaimed canoeists, skillfully navigating the treacherous Columbia River and bar to the amazement of the traders and explorers. We plied the coastal waters from California to Alaska in canoes (kaniN) twenty-one to forty-two feet long and larger, carved from a single Red Cedar log and propelled by our distinctly notched, crescent-shaped paddles (isik) of Oregon Ash. It was this skill of travel, which transformed us into a tribe of tremendous wealth and power.

We were highly acclaimed canoeists, skillfully navigating the treacherous Columbia River and bar to the amazement of the traders and explorers. We plied the coastal waters from California to Alaska in canoes (kaniN) twenty-one to forty-two feet long and larger, carved from a single Red Cedar log and propelled by our distinctly notched, crescent-shaped paddles (isik) of Oregon Ash. It was this skill of travel, which transformed us into a tribe of tremendous wealth and power.