|

Archive for June 26th, 2011

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

島に咲く花たち

いろんな花たちが咲き始めている。

島をまわる道路際には、シャク、エゾカンゾウ、チシマフウロがなど見られる。

のびてきている緑色の草の中に、群生している花たちを見つけて歩くことが楽しい。

海岸草原にはオレンジ色の花、エゾカンゾウが群生しています。

自然の花園の彩りは、いつも心を癒してくれます。

Pure white Wild Carrot (torilis japonicus) and bright orange Ezo-kanzou [Day Lily] grow in colonies in the meadows along the coast. The natural colors of the flowers always warm our hearts.

~~~ photos by Eiji Nishiya ~~~

Posted in FOM Japan, Gates Ajar, Home | Comments Off on Early Summer on Rishirito

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

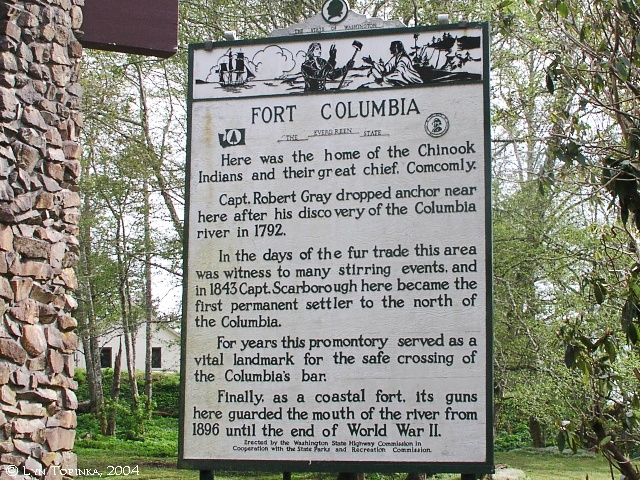

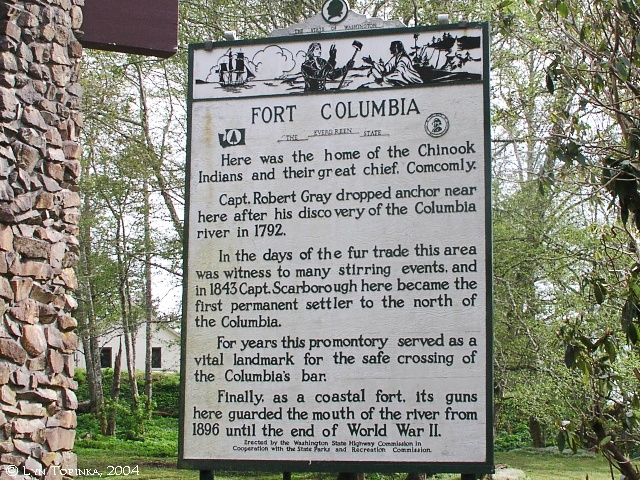

To help us appreciate the First Peoples of the Columbia River Basin …

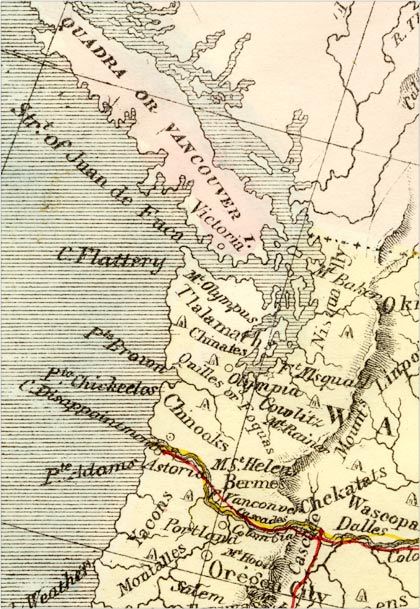

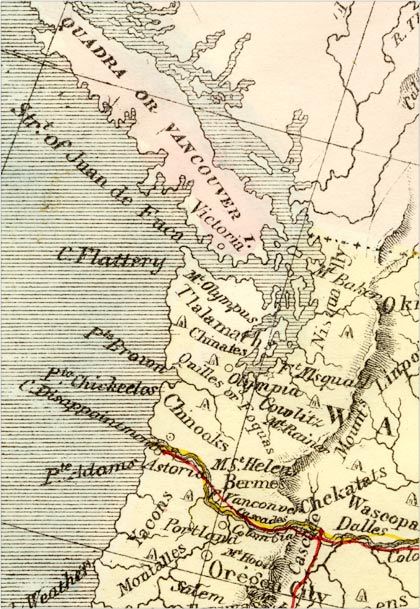

(Chinook, from Tsinúk, their Chehalis name). The best-known ‘tribe’ of the Chinookan family claimed the territory on the north side of the Columbia River from its mouth to Grays Bay, a distance of about 15 miles, and north along the seacoast as far as the north part of Shoal-water bay, where they were met by the Chehalis, a Salish tribe. The Chinook were first described by Lewis and Clark, who visited them in 1805, though they had been known to traders for at least 12 years previously(1) ~

“… This Chin nook Nation is about 400 Souls inhabid the Countrey on the Small rivrs which run into the bay below us and on the Ponds to the N W of us, live principally on fish and roots, they are well armed with fusees and Sometimes kill Elk Deer and fowl. our hunters killed to day 3 Deer, 4 brant and 2 Ducks, and inform me they Saw Some Elk Sign. I directed all the men who wished to See more of the main Ocian to prepare themselves to Set out with me early on tomorrow morning. The principal Chief of the Chinnooks & his familey came up to See us this evening …” [Clark, November 17, 1805] “… found maney of the Chin nooks with Capt. Lewis of whome there was 2 Cheifs Com com mo ly & Chil-lar-la-wil to whome we gave Medals and to one a flag. …” [ Wm. Clark, November 20, 1805 ]

Com’comly, grandfather of Ranald and the principle Chinook Chief of the time, received the Lewis and Clark expedition hospitably when it emerged at the mouth of Columbia River in 1805, and when, in 1810, the J.J. Astor Expedition arrived to take possession of the region for the United States, Com’comly cultivated a close friendship with the pioneers, even giving his daughter [Ilchee] as wife to Duncan McDougal, a Canadian fur trader who was at their head and who took part in the founding of Ft. Astoria in 1811.

Yet Com’comly may have been an accomplice in a plot to massacre the garrison and seize the stores. When a British ship arrived in 1812 to capture the fort at Astoria, Com’comly, with 800 warriors at his back, offered to fight the’ enemy’. The American agents, however, had already made a peaceful transfer by bargain and sale, and gifts and promises from the new owners [the North West Company] immediately made Com’comly their friend.(2) Writing in Aug., 1844, Father De Smet(3) states that in the days of his glory Com’comly, on his visits to Vancouver, would be preceded by 300 slaves, “and he used to carpet the ground that he had to traverse, from the main entrance of the fort to the governor’s door – several hundred feet – with beaver and otter skins.”(4)

The Chinookan nation was one of the most powerful native groups in Oregon. It included those tribes formerly living on the Columbia River, from The Dalles to its mouth (except a small strip occupied by the Athapascan Tlstskanai), and on the lower Willamette as far as the present site of Oregon City, Oregon. The family also extended a short distance along the coast on each side of the mouth of the Columbia, from Shoalwater bay on the North. to Tillamook Head on the South.

The region occupied by Chinookan tribes seems to have been well populated in early times. Lewis and Clark estimated the total number at somewhat more than 16,000. In 1829, however, there occurred an epidemic of unknown nature, which, in a single summer, destroyed four-fifths of the entire native population. Whole villages disappeared, and others were so reduced that they were, in some cases, absorbed into other villages. It can be assumed that it was the result of contact with a “white man’s” disease for which they had no immunity. The epidemic was most disastrous below the Cascades. In 1846 Hale estimated the number below the Cascades at 500, and between the Cascades and The Dalles at 800. By 1854 Gibbs gave the population of the former region as 120 and of the latter as 236. They were scattered along the river in several bands, all more or less mixed with neighboring stocks. In 1885 Powell estimated the total number at from 500-600, for the most part living on Warm Springs, Yakima, and Grande Ronde reservations in Oregon.

Most of the original Chinookan bands had no special tribal names, being designated simply as “those living at (place name)” This fact, especially after the epidemic of 1829, made it impossible to identify all the tribes and villages mentioned by early writers. Their language served as the basis for the Chinook Jargon which became the principal means of communication for the Indians from California to the Yukon, as well as trappers, traders and the majority of other individuals living and surviving in the territory.(5)

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Ranald MacDonald’s World – Chief Com’comly and the Tsinuk of the Lower Columbia

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

On July 20, 1811, Duncan McDougal, Chief Factor for the Pacific Fur Company at Astoria, Oregon, and Ilchee, daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook Tribe, married, becoming the first couple to be married in Astoria.

Washington Irving in his narrative Astoria (published in 1836) tells the tale:

“… M’Dougal, who appears to have been a man of a thousand projects, and of great, though somewhat irregular ambition, suddenly conceived the idea of seeking the hand of one of the native princesses, a daughter of the one-eyed potentate Com’comly, who held sway over the fishing tribe of the Chinooks, and had long supplied the factory with smelts and sturgeons. Some accounts give rather a romantic origin to this affair, tracing it to the stormy night when M’Dougal, in the course of an exploring expedition, was driven by stress of the weather to seek shelter in the royal abode of Com’comly. Then and there he was first struck with the charms of the piscatory (sic) princess, as she exerted herself to entertain her father’s guest.

The “Journal of Astoria,” however, which was kept under his own eye, records this union as a high state alliance, and great stroke of policy. The factory had to depend, in a great measure, on the Chinooks for provisions. They were at present friendly, but it was to be feared they would prove otherwise, should they discover the weakness and the exigencies of the post, and the intention to leave the country. This alliance, therefore, would infallibly rivet Com’comly to the interests of the Astorians, and with him the powerful tribe of the Chinooks. Be this as it may, and it is hard to fathom the real policy of governors and princes, M’Dougal dispatched two of the clerks as ambassadors extraordinary, to wait upon the one-eyed chieftain, and make overtures for the hand of his daughter.

The Chinooks, though not a very refined nation, have notions of matrimonial arrangements that would not disgrace the most refined sticklers for settlements and pin-money. The suitor repairs not to the bower of his mistress, but to her father’s lodge, and throws down a present at his feet. His wishes are then disclosed by some discreet friend employed by him for that purpose. If the suitor and his present find favor in the eyes of the father, he breaks the matter to his daughter, and inquires into the state of her inclinations. Should her answer be favorable, the suit is accepted and the lover has to make further presents to the father of horses, canoes, and other valuables, according to the beauty and merits of the bride; looking forward to a return in kind whenever they shall go to housekeeping.

We have more than once had occasion to speak of the shrewdness of Com’comly; but never was it exerted more adroitly than on this occasion. Com’comly was a great friend of M’Dougal, and pleased with the idea of having so distinguished a son-in-law; but so favorable an opportunity of benefiting his own fortune was not likely to occur a second time and he determined to make the most of it. Accordingly, the negotiation was protracted with true diplomatic skill. Conference after conference was held with the two ambassadors. Com’comly was extravagant in his terms; rating the charms of his daughter at the highest price, and indeed she is represented as having one of the flattest and most aristocratical (sic) heads in the tribe.

At length the preliminaries were all happily adjusted. On the 20th of July, early in the afternoon, a squadron of canoes crossed over from the village of the Chinooks, bearing the royal family of Com’comly, and all his court.

That worthy sachem landed in princely state, arrayed in a bright blue blanket and red breech clout, with an extra quantity of paint and feathers, attended by a train of half-naked warriors and nobles. A horse was in waiting to receive the princess, who was mounted behind one of the clerks, and thus conveyed, coy but compliant, to the fortress. Here she was received with devout, though decent joy, by her expecting bridegroom.

Her bridal adornments, it is true, at first caused some little dismay, having painted and anointed herself for the occasion according to the Chinook toilet; by dint, however, of copious ablutions, she was freed from all adventitious tint and fragrance, and entered into the nuptial state, the cleanest princess that had ever been known, of the somewhat unctuous tribe of the Chinooks.

From that time forward, Comcomly was a daily visitor at the fort, and was admitted into the most intimate councils of his son-in-law. He took an interest in everything that was going forward, but was particularly frequent in his visits to the blacksmith’s shop; tasking the labors of the artificer in iron for every state, insomuch that the necessary business of the factory was often postponed to attend to his requisitions. …”

Paul Kane wrote about Ilchee and Duncan McDougal in his Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, published in 1859:

“… [Ilchee] was the daughter of the great chief generally known as King Com’comly, so beautifully alluded to in Washington Irving’s “Astoria”. She was formerly the wife of a Mr. McDougall, who bought her from her father for, as it was supposed, the enormous price of ten articles of each description, guns, blankets, knives, hatchets, &c., then in Fort Astoria. Com’comly, however, acted with unexpected liberality on the occasion by carpeting her path from the canoe to the Fort with sea otter skins, at that time numerous and valuable, but now scarce, and presenting them as a dowry, in reality far exceeding in value the articles at which she had been estimated. On Mr. McDougall’s leaving the Indian country she became the wife of Casanov . . .” In 1813, when Astoria was turned over to the British, McDougal left. Ilchee eventually traveled up the Columbia to the Vancouver area and married Chief Casino (often seen as “Casanov”), a Chinook chief and successor to Chief Com’comly, before returning to her home at the mouth of the Columbia.

~~~

In 1823, in the ‘custom of the country,’ Archibald McDonald took a Native wife, Princess Raven – Koale’Koa – daughter of the influential Chinook chief Com’comly. Early in 1824 a son, Ranald, was born to them. Raven did not long survive the baby’s arrival, and Ranald was sent to live with his mother’s sister, Ilchee, in Com’comly’s lodge.

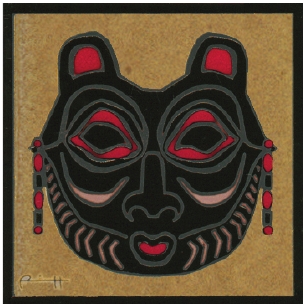

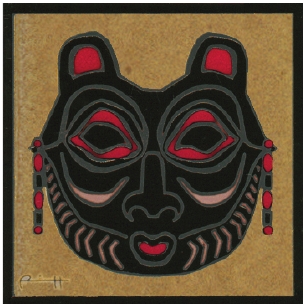

~~~ photo of Ilchee by Mas Yatabe

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on The Marriage of Ilchee and Duncan McDougal

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

“Once there were a people so wealthy, plump, and sleek that they drank sea lion oil straight and didn’t have to look for food all winter long. They danced and sang and recited stories instead. These people’s upriver neighbors bent under ninety-pound packs. These people just carried their big boat down to their river, piled in several tons of trade goods ( cranberry preserves, smoked salmon, dried clams, six or seven kinds of vegetables, fur robes, and arrow-proof battle armor ) and paddled a hundred miles or so up the river to trade.

They were not just rich but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows. but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

What to call these people is a problem. The name Wimah merely meant “Big River,” which was the same meaning all of the other three languages above the Chin on the river called it. But the people had no name at all for themselves. Each village had a name, and there were names for groups of villages that spoke the same dialect, but each village was really separate, indeed each family was separate, though inextricably connected by relationships to other families. A man might take his house planks and dependents, and paddle up to the next village, and then he was one of those people. As for a name for all those who spoke Chinookan languages, fifty or more winter villages strung along both banks of the lowest two hundred miles of the Columbia River, plus twenty-five miles up the Willamette River at the falls and the Clackamas River, and twenty miles north and south along the Pacific seacoast, for all those people the river people had no name, indeed hardly more than a memory that they must be related.

When the first European ship sailed into the river and anchored eight miles above the mouth, offshore from proud Qwatsamts, a three-row village, the mariners wanted to know what to call the people. One sailor asked some sort of question, in some approximation of language, pointing at the village. Something like, “What are these people called?” (Pointing, by the way, was dangerous and ill-mannered among these people.) A headman or spokesman responded Chinoak or Tsinuk or something like that. Forever after, the white people called the people in that village, and three or four others along the riverbank nearby, Chinook or Chinooks. (The river people at first called the strangers tlohonnipts, “those who float [or drift] ashore.”)

After a while, when they learned that the people upriver for a couple of hundred miles had roughly the same languages, the tlohonnipts called them Chinook, too. Years later, all canoe-paddling Indians on the North Pacific Coast were sometimes referred to as Chinooks. All that, based on no more than what some person answered when strangers impolitely pointed toward the village of long cedar-plank houses, row on row along the shore, which town they called Qwatsamts.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed. Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

In trade they were very like us, but in other ways they were utterly opposite. Our Western heritage contemplates a universe where there is one central God and all the subordinate creatures take their identities in relation to that over powering One. The Chinook believed the world a multiverse where everything was alive and had its own spirit. The powers of the spirits differed widely but there was no central all-powerful One.

The Chinook lived along the river for thousands of years. Then pale strangers floated ashore, and within forty years the Chinook were pretty much gone. All but a few in the center of their land disappeared, a great majority of those at the seacoast and Willamette Falls, a relatively smaller percentage at the eastern edge, up the Columbia River Gorge. In much of that area their culture was shattered.

Tsagiglalal saw all this happen, from her rock at the uppermost end of the Chinook-occupied river. Tsagiglalal is a beautiful broad face, with luminous eyes and wide smile, her tongue thrust out, inscribed on rim-rock at the easternmost edge of the Chinook land. Coyote, their myth age trickster-hero, put her there to watch the people. “She Who Watches” they called her. She became a symbol of conscience and of death. “She sees you when you come,” they said, “she sees you when you go.”

What, if anything, did the long persistence and swift collapse of the Chinook mean? They were living so nicely. They had all they wanted and nobody to bother them, were wealthy and respected. Then, because of the skin of a sea mammal and a host of spirits too small to see, thousands of them died, their culture crumbled and the survivors were sent away in a cruel diaspora.

They didn’t sign away their rainy Eden or sell it, they didn’t die in warfare, or move to reservations, not until twenty-five years after the catastrophes that swept most of them away. It wasn’t smallpox that laid them low. Suddenly most them were simply gone. The Wapato Lowlands in particular were empty and silent. Did God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

This book is meant to remedy that lapse of memory. Naked Against The Rain, Far Shore Press, Portland, OR, 1999.

***

She Who Watches has also been called the stone Owl Woman who watches. Indian women have gone to the stone and knelt before it. They would say something like, “You who watch, please look into me and see my problem and help me to solve it.” A ray of light would come down to shine on the stone face then. After the woman goes to her teepee to sleep a dream would come telling her how to deal with the problem. Maybe that woman would go again to the stone and the ray of light would come down again on the stone, and the next dream would give even more detail as to how to solve the problem.

From: Tahmahnaw, The Bridge of the Gods, by Jim Attwell.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on She Who Watches — Tsagaglalal ~ By Rick Rubin © 2000

|

|

|

but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows.

but highly intelligent and comparatively sane. Their numerous villages of fancifully decorated houses lined the shores of the mighty river, from which they drew most of their living and much of their pleasure. That river (we call it the Columbia) was all they ever wanted. It provided them with more than they could use. Fish in profusion swam up the river, which they called Wimah. Five of the six kinds of salmon that swim the Pacific Ocean, sturgeon, smelt, and lamprey came up, each in its season, to offer their succulent flesh to the people. Crabs and oysters in the bays, roots and bulbs in the marshes, deer, bear and elk in the forests and meadows. Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.

Tsinuk was what the Chehalis, who lived to the north and spoke an entirely different language, called the village or villagers, or some of the river people Chinook, or perhaps Chin people. For though it is probably only a coincidence, the suffix ooks or uks meant plural people in the Chinook language. So it is possible, though unlikely, that the people were really called the Chin, and Chinooks meant more than one Chin person. Of such shadows are names made, when strangers with no common language first meet. Personally, I favor Chin for its simplicity and the feel of it against the roof of my mouth, Tchinn. The language is how I categorized them, and on that account we might call them Chinookans, if the word sounded better to the ear. During their perhaps three or four thousand years of living along the Columbia one language evolved into three or more languages, with relationships about like Dutch to German, or Portuguese to Spanish, and there were dialects and mutually understandable accents, but in all the world, only the people of the river spoke a Chinookan language. Chinook or Chinookans or Chin, they were a singular people, far different from the stereotype “Indians.” They were polite anarchists (in the classic, not the modern sense) with artificially flattened heads and a tendency toward red hair, which they delighted in. They had a highly stratified society with many subtle variations of class. The Chinook had ritualized inter-village or tribal conflict into a maritime battle performance, where few were harmed and gifts were exchanged afterward. They were open to new people and ideas, true cosmopolites, and they loved more than anything to barter. They were good at it, too. The Chinook bettered the canny Scottish fur traders again and again, or so the Scottish fur traders claimed.