Ancient Drifters

Sunday, January 7th, 2024“The Hojun-Maru was not the ‘first’ but was, in fact, one of 100 known Asian drift boats that have crossed the Pacific accidentally. (The last one to arrive came ashore on the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1987, empty.)” – Daniel Wood, The Tyee

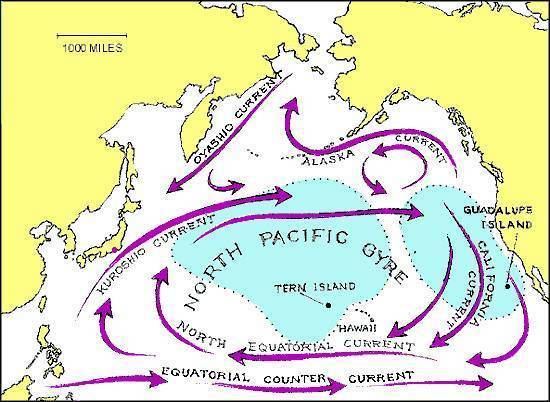

For most of us in the United States, no ocean current is better known than the Gulf Stream. It begins in the Gulf of Mexico, flows up the eastern seaboard, then crosses the Atlantic to Europe. Its warm waters help regulate temperatures across two continents. There’s an equivalent current in the western Pacific Ocean as well. It flows past Taiwan and along the eastern coast of Japan before turning toward the Pacific. It’s known as the Kuroshio Current. The name is a Japanese word that means “black stream” – because the current is much darker than the surrounding waters – the result of lower amounts of organic material at the surface.

The Kuroshio is the biggest current in the western Pacific. It begins off the coast of the Philippines, where a current that flows westward across the Pacific splits in two. The Kuroshio forms the northern branch. It travels almost 2,000 miles before it begins moving away from land. The current is strongest from May to August, with a smaller surge in winter. A recent study found that at its peak, it can be up to 50 miles wide, and flow at three or four miles per hour. Its average surface temperature is about 75 degrees Fahrenheit – several degrees warmer than the surrounding ocean. That helps keep southern Japan relatively warm. Over the centuries, the Kuroshio has carried many ships away from Japan. An extension of the current has then ferried some of them to Hawaii or even North America – a journey that began in the Gulf Stream of the Pacific. Kuroshio Current Jan. 3, 2016 By Damond Benningfield https://www.scienceandthesea.org/program/201601/kuroshio-current]]

Did Ancient Drifters ‘Discover’ British Columbia? Legends and bits of evidence tell a story of Asians arriving here long, long ago … by design or by chance. ~ Daniel Wood, 3 Apr 2012, TheTyee.ca

“As the tide creeps over the sand flats, estuaries and beaches of the Pacific Coast, from the northern Alaska Panhandle to the southern reaches of Baha California, it brings ashore the flotsam of the Pacific that – on occasion – hints at extraordinary travels and a mystery of historic proportions. Amid the kelp, in decades past, hundreds of green-glass fishing floats would arrive intact on the Vancouver Island coast, having ridden the powerful Japanese Kuroshio Current in year-long transits from Asia. On rare occasions, entire ships would arrive – like the derelict, Hokkaido-based, 54-metre squid-fishing boat located recently 260 kilometers off Haida Gwaii archipelago, part of the estimated 5 million tons of debris headed this way from the 2011Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami.

Even more rarely, ‘ghost ships’ would carry survivors of this slow drift, men who spoke Chinese, or Japanese. Such was the case of the Hyojun Maru (sic) that was left rudderless in a typhoon off Japan and drifted for 14 months before being washing up in 1834 on the Cape Flattery headlands. It contained three living sailors. It is, in fact, one of 100 known Asian drift boats that have crossed the Pacific by accident. (The last one to arrive came ashore on the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1987, empty.)

No one knows the source of early iron implements in the Pacific Northwest – where iron was unknown; or the origin of the 100 Asian plants and human parasites that suddenly appeared in Latin America a few millennia ago; or the recently revealed linguistic similarities between early Chinese-Tibetan and Mayan words. How did the bones of chickens – an Asian fowl from Samoa – get into a prehistoric American garbage pile? What explains the unmistakable links between Japanese and New Mexico Zuni First Peoples’ blood type, religion and language? These Asian influences appear to have arrived abruptly within the past 1,500 years.

Where does coincidence end and ‘fact’ begin? Were Asian watercraft crossing the Pacific long before Europeans crossed the Atlantic? The first clues to this supposition may have been reports from Bella Coola (Central B.C.) fishermen of glass Japanese fishing floats entangled in their nets. Could it be that the east-flowing ocean currents that were bringing Japanese fishing floats to Bella Coola also ‘accidently’ carried primitive vessels across the Pacific from Asia?

David Burley, chair of Simon Fraser University’s Department of Archeology, admits, “People moved from west to east across the Pacific. If the Polynesians hit tiny Easter Island [off Chile] – and they did – they had to hit South America. If they got to Hawaii – and they did – they got to the Pacific Northwest.” There are Ainu totem poles from northern Japan, he adds, that are almost identical to West Coast totem poles. There’s old Polynesian bark cloth that’s identical to native cedar cloth here. “

Maybe it’s time to follow the old myths, like the native myths of people arriving long, long before the appearance of the first Europeans. Like the Chinookan myths repeated to a boy named Ranald MacDonald.

The story starts when a disabled coastal trading vessel off central Japan drifted across the Pacific Ocean and “beached” on the Olympic Peninsula coast in early 1834 . . . The Hojun-Maru, with a crew of 14, set out on October 11, 1832 from the port of Onoura on the southeast coast of Japan, laden with a cargo of rice and porcelain. The ‘junk’ was caught in a typhoon, stripped of its rudder, and carried out to sea. After drifting for about 14 months across 5,000 miles of ocean, Hojun-Maru washed ashore. The precise location is unknown, but evidence points to Cape Alava, about 20 miles south of Cape Flattery, adjacent to the ancient Makah fishing village of Ozette. Left alive were the ship’s navigator, Iwakichi, age 28, and two apprentice cooks, Kyukichi, age 15, and Otokichi, age 14. Like most of the rest of the crew, they were from the village of Onoura, then a port city, now a beach resort. Their names are known in part because of a memorial erected by their fellow towns-people shortly after their ship disappeared. The three survivors promptly encountered a group of Makah seal hunters. Neither the Japanese nor the Makah would have had any idea that the other existed. Japan had been sealed off from the rest of the world for more than 200 years, and the Makah had had only limited contact with European fur traders. In any case, the Makah took command of the situation and claimed the sailors as captives.

Cape Alava on the NW coast of WA – could this be the beach where the Hojun-Maru castaway?

The Makah reportedly retrieved a number of items from the beached ship. [Fragments of ceramic bowls believed to have been on the Hojun-maru were later found on Makah land at Cape Alava.] Alexander C. Anderson, an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, reported meeting a group of Indians at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1834 who “produced a map with some writing in Japanese characters; a string of the perforated copper coins of that country; and other convincing proofs of a shipwreck”. But the Hojun-Maru apparently broke up and sank before much could be salvaged from it.[i]

[i] https://www.historylink.org/File/9068