The next post will definitely take on an ‘academic’ tone, sort of like what you’d find on The History Channel, but I think it is important to be able to place oneself shoulder-to-shoulder with Ranald MacDonald before one can really appreciate what it was like to live as a Metis – a half-European, half-Native American — in 19th Century North America [and beyond].

Many of us at Friends of MacDonald are familiar with the biography of MacDonald and can recite a near-litany of his many accomplishments, most particularly those events leading up to and including his clandestine entry into Japan in July of 1848. Though celebrated among those of us who know about his history as a world traveller and quasi-diplomat, in regards to his DNA, Ranald MacDonald was in no way unique.

When celebrating the history of the Celtic peoples in the New World, one must include the descendants of their liaisons with the First Peoples, for here is where we find many of the greatest stories on this continent. The joining of these two tribal cultures resulted in some of the greatest warrior-heroes to walk the planet – just when their people needed them the most. The traditional powers of the Old World (Britain, Spain and France) were locked in mortal combat over the vast resources of the New World. These “resources” included the “Coilltich“, the Gaelic word for the “forest-folk” – the term the Highlanders had for the Red Man.(1)

From the Gaelic periodical, Cuairtear nan Gleann, 1840, translated:

“There is no People on the face of this earth who, in matters of war or hunting, can surpass the Indians who inhabit the region of America not inhabited by the white people. They are now (alas!) few in number compared to what they were at one time; for, as the white people become more numerous and powerful, the Indians are scourged backwards before them, from place to place; and are injured by every sort of the most merciless brutality and violence.”

“The American Indians are very refined in their language and they are eloquent and expressive in their manner of speaking.”

It is possible that the Gaels realized that Native Americans were the disposed and disenfranchised of America in the same sense that the Gaels themselves had become the subject race of Scotland, driven out of their home by Clearances that continued into the early twentieth century.(2)

It is no wonder then, that the Highlander would leave the English on the coast of America and settle on the frontiers of the 18th and 19th centuries, intermingling with the tribes and settling down with the women of the First Peoples. “Such unions enabled them to enjoy better relations with their wife’s tribe, gave them a partner with the knowledge and experience necessary to survive in the wild, and bestowed full “native status” to their children on account of the matrilineal reckoning of Native American society.” Those children, who, having the bloodlines of two warrior tribes from different ends of the planet, made their indelible mark on history for both the Coilltich and the Ceiltich.(3)

To better understand Ranald’s story – who he was as well as his place in the history of this continent (and even in world history) it is important to understand and become familiar with what “his” world was like. This article will be the first in a series of articles that will hopefully provide some meaningful background to help us all better empathize with the “Life and Times” of Ranald MacDonald.

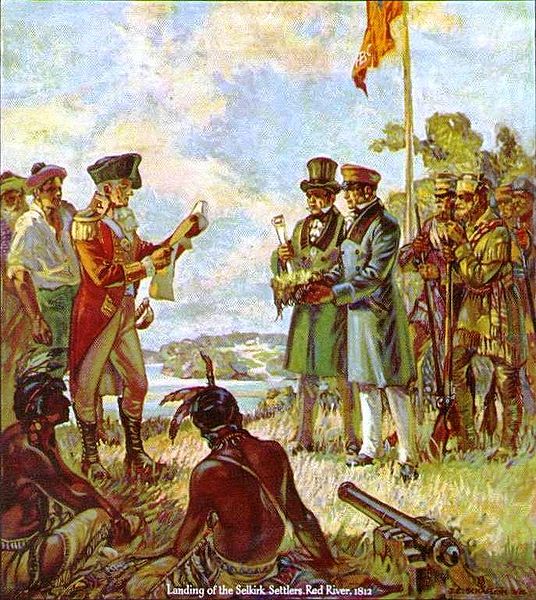

Landing of the Selkirk Settlers, Red River, 1812, J.E. Schaflein HBC’s 1924 calendar illustration, H.B.C. Archives

The fur trade – and the subsequent arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Company – had various effects on the northern First People [indigenous] populations from the Oregon Territory on the Pacific coast to the northwestern portion of the Northwest Territories and across South and Central Canada. The fur trade itself had already disrupted previous economic relationships between indigenous groups, and in some examples the presence of the Hudson’s Bay Company furthered tension between these groups as each vied for the control of fur-rich regions and sole access to specific Company posts. Though the Tribes may have competed with each other, due to the frontier nature of the region, the relations between fur trade companies and First Peoples was, by necessity, generally one of mutual accommodation. [This was in stark contrast to other European-First People relations.] The fur trade was dependent on indigenous trappers. This dependence resulted in a certain amount of respect for the ability of the indigenous trappers to locate fur-rich areas. Merchant firms such as the Hudson’s Bay Company were subject to market competition, and this in itself encouraged “fair behavior”. Another factor was that the White Traders and the First Peoples were too dependent upon each other to allow any type of extensive exploitation to occur.

The first large wave of Scottish immigration to Canada occurred between 1770 and 1815, when some 15,000 individuals moved to places like the Selkirk Settlement in current-day Manitoba, as well as to settlements along the East Coast and eastern Ontario. A significant number during the fur trade were men, and many of them would settle with Aboriginal women to create the Métis. During the great wave of immigration to Canada’s West during the 1800s and early 1900s, the Highlanders were the preferred group of immigrants because of their hardiness and their adaptability to farming, and these men were highly sought after. Archibald McDonald, Ranald’s father, was just such a man.

Winter Sunlight on Glencoe and Loch Leven ~ Copyright Jim Stewart

Archibald McDonald was born at Leeckhentium, on the southern shore of Loch Leven, Glencoe, Appin, in North Argyleshire, Scotland, on February 3rd, 1790. [His paternal grandfather, Iain (or John) McDonald, had been one of the few male survivors of the Massacre of Glencoe** in 1692.] It is said that Archibald was well educated and studied the rudiments of medicine at the University of Edinburgh before immigrating to Canada as a member of Lord Selkirk’s Colony(4) at Red River (Manitoba) in 1813, where he assumed a considerable share in the management of the Colony’s affairs, in part because he could act as an interpreter between the overseers of the colony, who spoke English, and the settlers, who, like him, were native Gaelic-speakers. [Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771~ April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk and was part-owner of the Hudson Bay Company.]

After Lord Selkirk’s death in 1820, his executors administered the colony, and sought to reduce expenses by ending settlers’ subsidies and refusing to recruit new European immigrants. Consequently, population growth came largely through the retirement of fur traders and their native families to the colony, encouraged by the newly-formed Hudson’s Bay Company’s reduction of the number of its employees. In the spring of 1820 Archibald entered the service of the H.B.C., shortly after the union of the H.B.C. and the North West Company; in 1821 H.B.C. Governor George Simpson sent McDonald to the Columbia district, on the Pacific Northwest coast, where he first served as accountant at Fort George [Fort Astoria].

It was at Fort Astoria in 1823 that Archibald was married “according to the custom of the country”, to the princess Koale’zoa (also known as Raven or Sunday) (d. 1824), daughter of Chinook chief Comcomly, with whom he had one son, Ranald McDonald; Archibald married a second time in 1825, also according to the custom of the country, Jane Klyne, a Metis [mixed-blood] woman with whom he had twelve sons and one daughter.(5)

McDonald was one very busy man; we might even be tempted to call him an ‘over-achiever’. At the very least his resume` is impressive. The following information is taken from Archibald McDonald: Biography and Genealogy, an article written by William S. Lewis and published in the Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 1918 : “In 1824 Archibald McDonald was one of the clerks in charge of posts in the Thompson’s River District, also known as the Columbia District. He succeeded John McLeod, Chief Trader, at Kamloops in the Thompson’s River District, in 1826.(6) In July 1828 he accompanied Governor George Simpson of the H.B.C. on a canoe voyage from York Factory, Hudson’s Bay to Fort Langley, New Caledonia, where he succeeded James McMillan.(7) He remained at Fort Langley until the spring of 1833. While stationed there he inaugurated the business of salting and curing salmon for market. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 15, 1831, McDonald wrote: “Our salmon, for all the contempt entertained for everything outside of the routine of beaver at York Factory, is close up to 300 barrels.”(8)

In 1833 he suggested the idea of raising flocks and herds on the Pacific Coast.

McDonald left Fort Langley for Fort Vancouver and on May 1833 selected the site and helped lay the foundation of Nisqually House [near present-day Tacoma, WA.] In July of that year he accompanied William Connolly up the Columbia with supplies for the interior, for the purpose of proceeding overland to enjoy a furlough. He spent 1834-35 in Scotland. Returning in the spring of 1835, he took charge of Fort Colville in 1836.(9) McDonald was stationed at Fort Colville from 1836 to 1843. In 1842 he was promoted to Chief Factor. While in the Columbia River district, Archibald had charge of and was eminently successful in placing the land in cultivation, and acquiring and raising horses, cattle, sheep, etc. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 25, 1837, McDonald states, “Your three calves are up to 55 and your 3 grunters would have swarmed the country if we did not make it a point to keep them down to 150.”(10)

Writing in September, 1837, Rev. Elkanah Walker thus describes Archibald McDonald’s farming operations at Fort Colville:

“It was truly pleasing after being nearly half a year without seeing anything that will bear to be compared with good farming, to see fenced fields, houses and barns grouped together, with large and numerous stacks and grain, with cattle and swine feeding on the plain in large number. There is more the appearance of civilized life at Fort Colville than any place I have seen since I left the States, and more than you see in some of the new places in the States … Mr. McDonald raises great crops. He estimates his wheat this year at 1500 bushels and his potatoes at 7000 bushels. Corn is in small quantity in comparison with his other grains.”

While at Fort Colville, in the early forties, Archibald McDonald is said to have had many hundred acres under partial cultivation. His son, Benjamin, stated that his father had nearly five thousand acres of land under cultivation at one time in the vicinity of old Fort Colville. Mr. Jacob A. Meyers places the maximum of land in agricultural use by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the vicinity of Fort Colville at 2000 acres, including in this estimate hay lands some twelve miles distant in the neighborhood of the present town of Colville. The company also held six townships of pasture lands obtained from the Indians by treaty.(11) [In his later years, Archie’s son Ranald panned the creeks flowing into the Kettle River and Boundary Creek in search of gold; Ranald died on the Colville reservation in 1894 in the arms of his niece, Jenny Lynch, the daughter of his half-brother Benjamin.](12)

At Fort Colville, Archibald supervised the reconstruction of the old sawmill, said to have been originally built in 1826-9, and the first sawmill on the Pacific Coast north of California. The original roof boards of the old fort buildings, of mill-sawn lumber, and lumber for company boats, bateaux and other purposes came from this mill. McDonald also supervised the rebuilding of the gristmill on “Mill Creek” (now Meyers Falls of the Colville River).

During Archibald McDonald’s many years in the Northwest he made no less than 15 trips across the continent between 1812 and 1845. He also kept very accurate journals, describing the country as regards to topography, soil, timber, rivers, climate, etc., through plains and over mountains, from Hudson’s Bay and the Great Lakes to the Pacific.

On his retirement from the H.B.C. in 1844 he moved overland with his family to Montreal, where he resided for two years. He then moved to St. Andrews on the Ottawa River, where he purchased a large tract of land and established a permanent home. He called his residence “Glencoe Cottage” and here he continued to live until his death on January 15, 1853, at the age of 62 years. Sadly, he may have died believing that his eldest son Ranald had perished at sea, though according to Fred Schodt in Native American in the Land of the Shogun, “ … this was unlikely. On April 3, 1852, the month before he removed Ranald from his will, Archibald wrote to a relative in Ft. Colville: ‘From Ranald, the Hero of Japan, I had several letters since his withdrawal from Jedo (sic) – He sticks to the sea, and last sailed from London for Sidney. But I trust now he will prefer digging for gold in Australia to the precarious and uncertain life of a sailor.’ ”

In the business of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archibald displayed great initiative and energy, and, possessing also considerable executive and business ability, he was unquestionably one of the most capable chief traders in the Columbia River District. Moreover, Archibald McDonald was a likeable character. He was naturally of a kindly nature, and a most agreeable companion. During his many years in the Northwest he maintained an extensive correspondence with his contemporaries in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service. To visitors at his post he was a most courteous host. John McLean, writing in April, 1887, says, “We met with a most friendly reception from a warm hearted Gael, Mr. McDonald.”(13) Reverend Elkanah Walker, in his Journal, under date of September 17, 1888, writes of his arrival at Fort Colville, “Received a cordial welcome from Mr. McDonald and lady.” Subsequent pages of the Journal record many courtesies and kindnesses of the Hudson’s Bay Chief Trader.(14)

His family relations were ideal, and he at all times displayed a patient and earnest regard for the spiritual and temporal welfare of his children, to all of whom he gave such educational advantages as his means and the times permitted. “It is high time,” he writes, “for me to see and get my little boys to school – God bless them – I have no less than five of them all in a promising way.”(15) A highlander born and bred, Archibald McDonald was in the best sense of the term “a gentleman of the old school,” a man utterly fearless, and of greatest personal integrity and honor. McLeod in his Peace River (pp. 117, 91) describes him as “a gentleman of utmost suavity of spirit as well as form.”

“As the twig is bent, so grows the tree.” It seems that in this, Ranald MacDonald had a superior role model in the form of his father.

To be continued … ~A.M.Y.~~~

(1)The Legacy of Scottish Highlanders in the United States ~Michael Newton 2001 (2)Ibid. [3]Mike Dunlap, from the upcoming book, “New World Celts: Voyage to America”[4]Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771 — April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk[5]Jean Murray Cole, Dictionary of Canadian History On Line[6]McLeod’s Peace River[7]See Archibald McDonald’s Journal; McLeod’s Peace River[8]Washington Historical Quarterly, i, 265, July, 1907.[9]Washington Historical Quarterly/, ii, 254, April, 1908;[10]Ibid [11]Lieutenant Johnson gives the cultivated land in the immediate vicinity of the fort (1841) as but 130 acres. U. B. Exploring Exp., iv, 443.[12]Washington State History, Native Americans in Ferry County[13]John McLean, Notes of a Twenty-Five Years’ Service in the Hudson’s Bay Territory [14]Reports of the U. S. (Wilkes Expedition (1841), IV, 443, 454[15]Washington Historical Quarterly, ii, 163, January, 1908