Station Camp and Clark’s Dismal Nitch

Thursday, September 15th, 2011Clark’s Dismal Nitch

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson dispatched Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead the Corps of Discovery on a mission to find a water route across North America and explore the natural resources of the uncharted American West. Little did Lewis and Clark realize that the time they would spend on the shores of the lower Columbia River would be counted among the most discouraging, dangerous, and disagreeable experiences faced during their expedition.

Imagine this: it’s early 1805, the fresh food had run out. The clothes were literally rotting off the backs of the members of the Corps of Discovery. They were traveling as fast as they could down the Columbia River, hoping to meet one of the last trading ships of the season. If they made it, they’d send a set of journals and some collections home as requested by President Jefferson. But foremost was the chance to use an unlimited letter of credit from the president, a chance to “charge” all the goods the tired explorers needed [plus perhaps get a little rum] from the trade ship.

What the Corps didn’t realize, however, was that it was about to run into some of the journey’s most treacherous moments. A fierce winter storm forced the Corps off the river and pinned the group to a north shore cove consisting of little more than jagged rocks and steep hillside. On November 10th, as the party paddled past Grays Point, they saw that the steep, forested shoreline consisted of a series of coves, or “nitches”, each divided from the next by a small point of land. They passed present-day Dismal Nitch (also known as Megler Cove), but as the weather again worsened, the party retreated to a sheltered cove upriver from the Dismal Nitch, [approximately 600 feet north / northeast of the eastern end of the present-day “Dismal Nitch Safety Rest Area”].

Rain soaked the expedition party that night, and it continued at intervals throughout the next day, November 11, 1805. Conditions worsened on November 12th; on top of rain, wind and cold came thunder, lightning and hail. Clark describes their move from the unnamed cove to the Dismal Nitch:

“As our situation became Seriously dangerous, we took the advantage of a low tide & moved our Camp around a point a Short distance to a Small wet bottom at the mouth of a Small Creek (Megler Creek), which we had observed when we first came to this cove…”

The rain continued on November 13 and 14. For only the second time in the expedition, Clark said he was concerned for the safety of the Corps. “A feeling person would be distressed by our situation,” he wrote in wet misery, as the expedition became in danger of foundering just within a few miles of its destination – the Pacific Ocean. Finally, the storm broke and allowed the group to move on. It missed the trading ship, but eventually achieved its exploration goals. On the morning of November 15 Clark awoke to calm weather for the first time in 10 days. Clark describes the party’s escape from what became known as “the Dismal Nitch”:

“About 3 oClock the wind lulled and the river became calm, I had the canoes loaded in great haste and Set Out, from this dismal nitich where we have been confined for 6 days…”

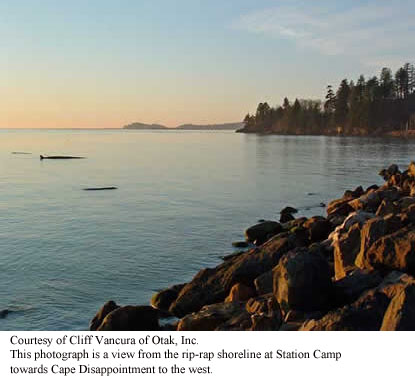

Although the Corps met “near disaster” at Dismal Nitch, they arrived “in full view of the ocian” at Station Camp. [It was at Station Camp that the famous vote was taken that included all members of the party and the party decided to move the south shore of the Columbia River where they would spend the winter before beginning their long journey home: more about this later.] However, both before and after Captains Lewis and Clark established Station Camp, the site was a vital and thriving Chinook Indian village. The Corps spent just 10 days here, but used Station Camp as a departure point for an overland trek to their first view of the Pacific Ocean and an exploration of the area. Together with nearby Dismal Nitch, Station Camp helps greatly to tell the Lewis and Clark story in Washington – and the ultimate effect the Corps of Discovery had upon the indigenous First peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

For thousands of years, the Chinook people have lived along the Columbia River and their home near the river’s mouth was strategically located to provide abundant food, such as salmon and shellfish. In addition, the nearby forests were home to game animals and the grasslands and marshes provided ample materials for making shelter, clothing and trade and household goods. The river provided a way for Chinook traders to travel to the south shore and up and down the Columbia.

Generations before the White Explorers came, the Chinook had already developed a sophisticated, rich culture and enjoyed great success as traders. The waterway near Station Camp became a virtual trade “water highway.” During the 10 years before Lewis and Clark arrived overland at this spot, almost 90 trade ships from Europe and New England are documented to have crossed the Columbia River Bar to trade with Native Americans. These ships brought metal tools, blankets, clothing, beads, liquor and weapons to trade for beaver and sea otter pelts. By the time the Corps reached the site, the Chinook’s had moved to their winter village and this village was unoccupied. The explorers spent almost two weeks there.

Several significant events took place, including the decision to spend the winter across the river, in what is now Oregon. It was Nov. 24, 1805, and the explorers desperately needed to lead the Corps to a winter campsite, one rich with game and near friendly tribes who would trade for supplies. A majority of the Corps, including the Indian woman Sacagawea and the African American York decided to cross the Columbia River to look for such a place. Because of this poll and decision, some historians call Station Camp “the Independence Hall of the American West.” It would be more than fifty years before African Americans could vote, and more than 100 years before the right was extended to women.

History of “Dismal Nitch”

The Dismal Nitch area is located within the traditional territory of the lower Chinookan people. Through common usage, the term Chinook has come to refer to all speakers of the Chinook language family who inhabited the territory from the mouth of the Columbia River upstream to The Dalles and along the lower Willamette River to present-day Oregon City.

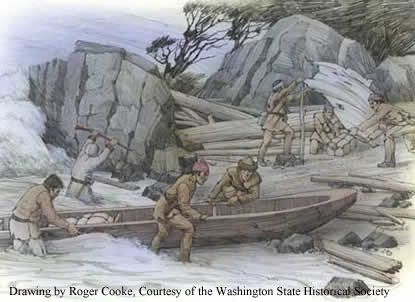

Of the many Chinook villages along the north shore of the Columbia River, two known summer villages were located in the vicinity of the Dismal Nitch. Approximately 1.25 miles southwest of the Dismal Nitch was Qaiitsiuk, later called Chinookville or Chenook, just west of present-day Point Ellice. The Lower Chinook were known for their canoe-building prowess, and their vessels helped them establish their reputation as traders well before Europeans set eyes on the region.

The Lower Chinook were first described in writing by Captain Robert Gray, who sailed into the mouth of the Columbia River in 1792, and by Captain George Vancouver, who also sailed into the area that year. By the time Lewis and Clark descended the river in the fall of 1805, the presence of Europeans on the lower Columbia River was not uncommon.

Today, the Chinook Indian Nation is made up of five separate tribes, including the Chinook, the Willapa, the Clatsop, The Kathlamets, and the Wahkiakum. All five tribes are Chinookan speakers.

The State of Washington is developing a park at Middle Village – Station Camp, focusing on the Chinook history, as well as telling the story of the Corps’. In 2005, archeologists found abundant physical evidence to support the importance of the site as a Chinook trade village. More than 10,000 artifacts were uncovered, including trade beads, plates, cups, musket balls, arrowheads, Indian fish net weights and ceremonial items. The European artifacts are from both before and after the Corps’ visit in 1805, and attest to the vitality of the Chinook social and economic life at the site. Station Camp eventually will encompass about 280 acres and be operated by the Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Station Camp http://www.nps.gov/lewi/planyourvisit/stationcamp.htm

History of "Dismal Nitch” http://www.nps.gov/lewi/planyourvisit/dismal.htm