150 years ago, the world had yet to discover Japan, and the people of Japan had never seen America …

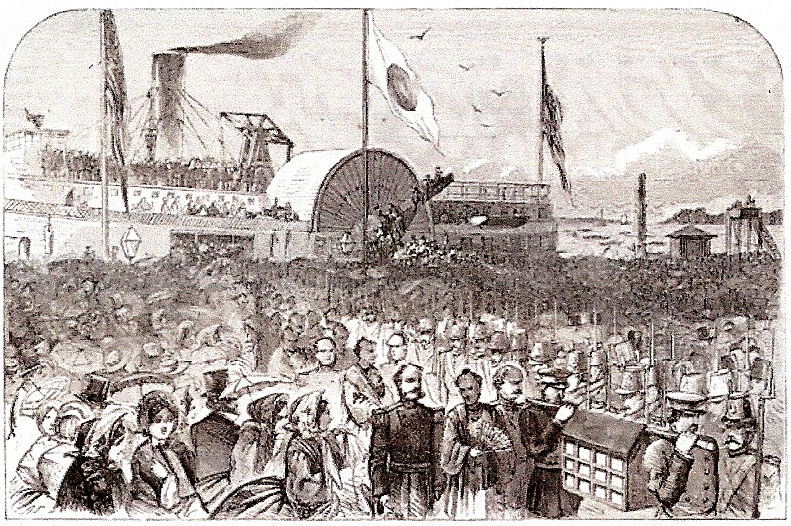

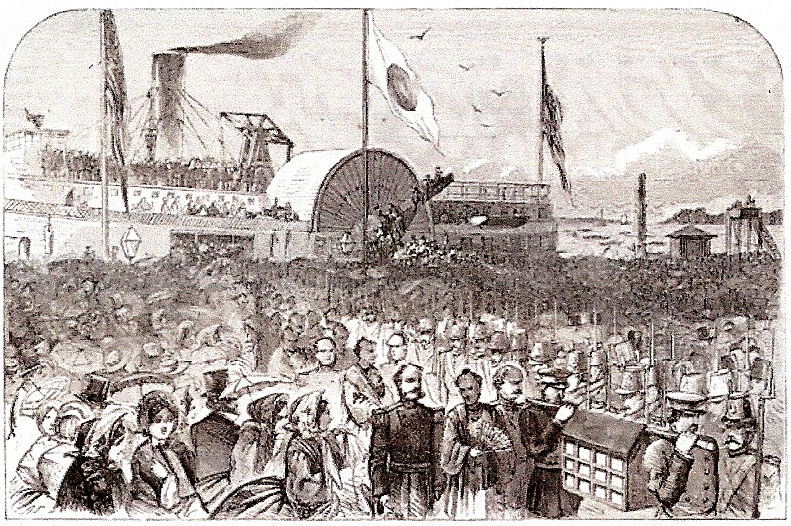

In the summer of 1860, before the Civil War erased all thoughts of international affairs from America’s mind, the Japan’s Tokugawa government sent its first diplomatic mission to the United States: a group of 77 samurai whose purpose was to exchange the instruments of ratification of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1858). The agreement opened the ports of Edo and four other Japanese cities to American trade, among other stipulations. In the years before the Civil War, the Japanese visitors captivated the American people and the press. Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Throughout their seven-week tour, the guests from Japan were greeted with great excitement, if not outright curiosity given their “exotic” dress and demeanor. Everywhere they went, they were met by overflowing crowds, and impressive parades were staged in their honor. The historic visit was widely covered in the American press of the day, which relished recounting every detail of the visits made by these exotic visitors. In fact, these Japanese envoys from across the Pacific became celebrities who captivated much attention across a nation that had yet to experience the outbreak of the American Civil War. This remarkable encounter of cultures was described in the June 11, 1860 edition of The New York Times as “… an event which, if it have any significance at all, involves consequences the most momentous to the civilization and the commerce of the world for ages to come.”

USS Powhatan carrying the First Japanese Embassy to America, circa 1860. Woodblock print, ink and colors on paper. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, CA (The U.S. frigate Powhatan was the so-called “Black Ship” formerly under the command of Commodore Perry)

This momentous event was not only a first for Japan, but for the West as well. Before the Japanese Embassy’s arrival on American shores, no Western country had ever received a diplomatic mission from East Asia. The significance of this great honor was not lost on the fledgling American republic. Congress adjourned for their arrival at the Navy Yard, while a crowd of 5,000 gathered to greet the samurai at the docks. Another 20,000 Washingtonians – Washington’s population at that time was about 75,000 – cheered along their route to the Willard Hotel, where the samurai would lodge during their stay. Men and boys climbed trees to get a better look as ladies tossed flowers from crowded, second-story windows.

Vice Envoy Muragaki described the scene in his private journal:

“What immense crowds there were! The streets were like seas of human beings; the windows and balconies were thronged with people eager to get a glimpse of the procession. I could not help smiling at the wonder in their eyes, which reached a culminating point when they caught sight of our party wearing costumes that they had never seen before or even dreamt of. I might say that the whole procession seemed to the people of Washington to be a scene out of fairyland, as, indeed, their city appeared to us.

It was however, not without a feeling of pride and satisfaction that we drove, in such grand style, through the streets of the American metropolis, as the first Ambassadors that Japan had ever sent abroad, and that we witnessed the enthusiastic welcome accorded to us by the citizens.”

Herman Melville called Japan “impenetrable” in Moby Dick (1851), and predicted that “(if) that double-bolted land, Japan, is even to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone to whom the credit will be due; for all ready she is on the threshold.” Less than three years later Commodore Perry’s steam-powered “Black Ships” [which included the U.S. frigate Powhatan] lowered their anchors in Edo Bay in 1853 and Japan’s official policy of national isolation, which had been followed for over two centuries, did indeed come to an end.

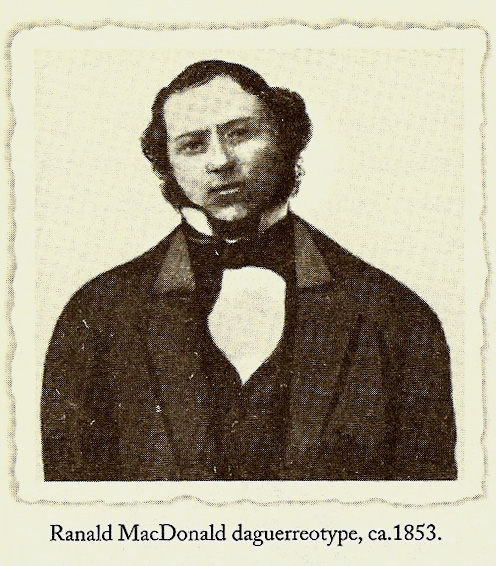

When I Googled “1860 Japanese ambassadors to America” over 90,300 results appeared. Of course I did not visit each and every website, but I did peruse the first four pages totaling just under 40 links. For Japanophiles the very idea that 90,000+ pages were devoted to one subject, e.g., the first Japanese embassy to visit America, is gratifying. For Friends of MacDonald members, however, the sparkles of delight are definitely muted; nearly every web article I inspected lovingly pointed out that Commodore Perry had “opened” Japan a mere 7 years before the official Japanese embassy visit, but none – NOT ONE – made mention of the fact that it had been Ranald MacDonald’s efforts – his design, if you will -that had facilitated the success of America’s first official contact with Japan, but Ranald had clearly articulated his intent, to wit:

“Wonder in an ocean of wonders! – to us, on its opposite shore, gazing, searching into the far, far offing, it was ever an object of intense curiosity. What of such people? What of their manner of life? What of their unrivalled(sic) wealth with its gleam of gold and things most precious? What of their life, social, municipal and national? What of their feelings and tendencies – if any – toward association or friendly relations with other people, especially us, neighbors of their East?

These and such like questions and considerations ever recurring; the subject, oft, of talk amongst my elders … entering deeply into my young and naturally receptive mind; breeding, in their own way, thoughts and aspirations which dominated me as a soul possessed. I resolved, within myself, to personally solve the mystery, if possible, at any cost of effort – yea, even life itself.

Satisfied in my own conscience with my purpose, I never abandoned it. That purpose was to learn of them; and, if occasion should offer it, to instruct them of us.” ~~ Ranald MacDonald, The Narrative of His Life, 1824-1894; pg.131 (annotated and edited by Wm. Lewis & N. Murakami)

And so he did. And if Ranald had not had the opportunity – and the audacity – to instruct several, bright Japanese students in the complexities of the English language – among them the Emperor’s eventual chief interpreter to Commodore Perry, Einosuke Moriyama – who knows how America’s initial foray into Japan would have turned out?

***

Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here:

Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here:  Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600

Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600 t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there.

t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there.