|

February 28th, 2011

ゴマフアザラシ

海岸の岩場で日向ぼっこするゴマフアザラシ。

近づいて行くと

「どうしたの、何かあったの?」と、聞かれた。

「シバレルね」と応えると

「そんなことないよ」と言って、岩場を降りていった。

I spied a spotted seal “sunbathing” on the rocks.

As I approached he asked, “Can I help you?”

“It’s really cold, isn’t it?” asked I.

“Not for me,” he answered as he slid into the icy sea.

photo and 'poem' by Eiji Nishiya, FOM, Rishiri Island

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Seal on the Rocks

February 3rd, 2011

日の入り

二月三日は月暦正月朔。

一年の初めに紅く丸く、海に入る日の入り。

利尻山頂が紅く映えていた。

明日は立春。春の気立つ日。

今年は暖かく晴n日が続くのだろうか。

“The sun is entering the ocean.”

“The red and round sun goes in to the ocean for the last time this year” … Rishiri mountain in the alpenglow of sunset on the last day of the year [according to the old-style, Japanese lunar calendar.] Tomorrow, February 3rd, is “risshun” [considered the first day of spring in Japan]. The “sense” of spring begins. I wonder if we will be blessed with warm, sunny days? ~Eiji Nishiya

Today is also the eve of Ranald MacDonald’s (187th) birthday.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Last Rishiri Sunset of the (old) Year

January 17th, 2011

Winter surf on Rishiri-to. Looks pretty cold, doesn’t it? Photo courtesy of Eiji Nishiya, Curator Rishiri Museum

The latitude of Rishiri Island is 45.15 degrees north — Ft. Vancouver is 45.30 degrees north [a coincidence, certainly, but an interesting bit of trivia nonetheless]. Many thanks to Mr. Eiji Nishiya, curator of the Rishiri Museum and Secretary of FOM Japan – and most excellent photographer! – for his many contributions to our web pages.

オオワシを見た。

ここ数年渡来している場所。

高い所から何を見ているのだろうか。

I watched a giant white-tailed eagle return

to the same place she’s been coming in recent years …

I wonder what she’s looking at from that high perch?

~Eiji Nishiya

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Winter on Rishiri-to

January 17th, 2011

The next post will definitely take on an ‘academic’ tone, sort of like what you’d find on The History Channel, but I think it is important to be able to place oneself shoulder-to-shoulder with Ranald MacDonald before one can really appreciate what it was like to live as a Metis – a half-European, half-Native American — in 19th Century North America [and beyond].

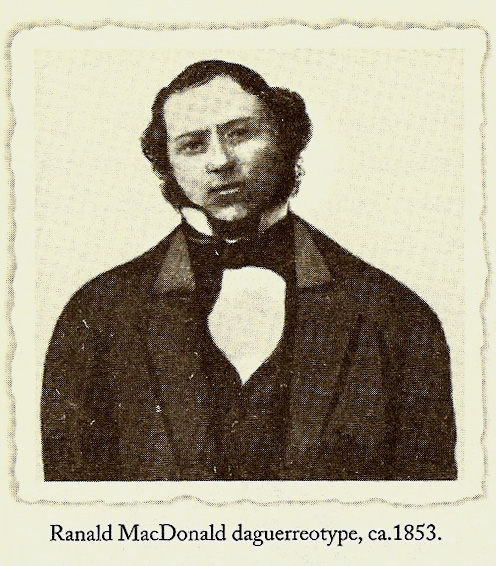

Many of us at Friends of MacDonald are familiar with the biography of MacDonald and can recite a near-litany of his many accomplishments, most particularly those events leading up to and including his clandestine entry into Japan in July of 1848. Though celebrated among those of us who know about his history as a world traveller and quasi-diplomat, in regards to his DNA, Ranald MacDonald was in no way unique.

When celebrating the history of the Celtic peoples in the New World, one must include the descendants of their liaisons with the First Peoples, for here is where we find many of the greatest stories on this continent. The joining of these two tribal cultures resulted in some of the greatest warrior-heroes to walk the planet – just when their people needed them the most. The traditional powers of the Old World (Britain, Spain and France) were locked in mortal combat over the vast resources of the New World. These “resources” included the “Coilltich“, the Gaelic word for the “forest-folk” – the term the Highlanders had for the Red Man.(1)

From the Gaelic periodical, Cuairtear nan Gleann, 1840, translated:

“There is no People on the face of this earth who, in matters of war or hunting, can surpass the Indians who inhabit the region of America not inhabited by the white people. They are now (alas!) few in number compared to what they were at one time; for, as the white people become more numerous and powerful, the Indians are scourged backwards before them, from place to place; and are injured by every sort of the most merciless brutality and violence.”

“The American Indians are very refined in their language and they are eloquent and expressive in their manner of speaking.”

It is possible that the Gaels realized that Native Americans were the disposed and disenfranchised of America in the same sense that the Gaels themselves had become the subject race of Scotland, driven out of their home by Clearances that continued into the early twentieth century.(2)

It is no wonder then, that the Highlander would leave the English on the coast of America and settle on the frontiers of the 18th and 19th centuries, intermingling with the tribes and settling down with the women of the First Peoples. “Such unions enabled them to enjoy better relations with their wife’s tribe, gave them a partner with the knowledge and experience necessary to survive in the wild, and bestowed full “native status” to their children on account of the matrilineal reckoning of Native American society.” Those children, who, having the bloodlines of two warrior tribes from different ends of the planet, made their indelible mark on history for both the Coilltich and the Ceiltich.(3)

To better understand Ranald’s story – who he was as well as his place in the history of this continent (and even in world history) it is important to understand and become familiar with what “his” world was like. This article will be the first in a series of articles that will hopefully provide some meaningful background to help us all better empathize with the “Life and Times” of Ranald MacDonald.

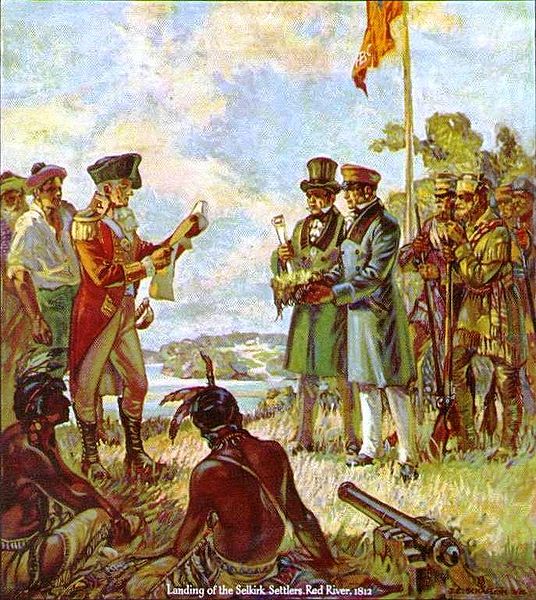

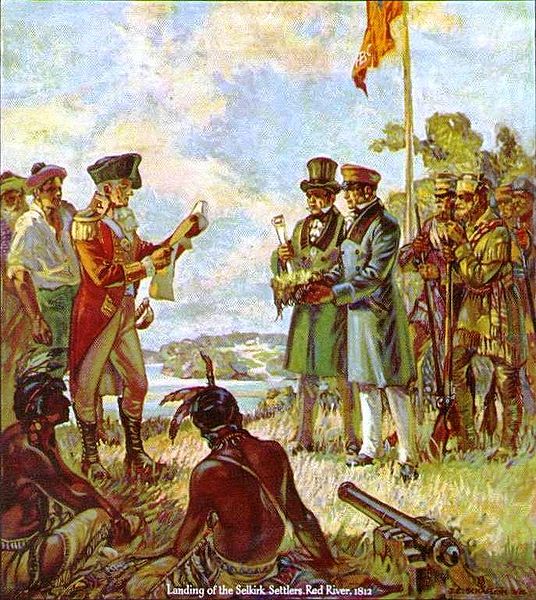

Landing of the Selkirk Settlers, Red River, 1812, J.E. Schaflein HBC’s 1924 calendar illustration, H.B.C. Archives

The fur trade – and the subsequent arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Company – had various effects on the northern First People [indigenous] populations from the Oregon Territory on the Pacific coast to the northwestern portion of the Northwest Territories and across South and Central Canada. The fur trade itself had already disrupted previous economic relationships between indigenous groups, and in some examples the presence of the Hudson’s Bay Company furthered tension between these groups as each vied for the control of fur-rich regions and sole access to specific Company posts. Though the Tribes may have competed with each other, due to the frontier nature of the region, the relations between fur trade companies and First Peoples was, by necessity, generally one of mutual accommodation. [This was in stark contrast to other European-First People relations.] The fur trade was dependent on indigenous trappers. This dependence resulted in a certain amount of respect for the ability of the indigenous trappers to locate fur-rich areas. Merchant firms such as the Hudson’s Bay Company were subject to market competition, and this in itself encouraged “fair behavior”. Another factor was that the White Traders and the First Peoples were too dependent upon each other to allow any type of extensive exploitation to occur.

The first large wave of Scottish immigration to Canada occurred between 1770 and 1815, when some 15,000 individuals moved to places like the Selkirk Settlement in current-day Manitoba, as well as to settlements along the East Coast and eastern Ontario. A significant number during the fur trade were men, and many of them would settle with Aboriginal women to create the Métis. During the great wave of immigration to Canada’s West during the 1800s and early 1900s, the Highlanders were the preferred group of immigrants because of their hardiness and their adaptability to farming, and these men were highly sought after. Archibald McDonald, Ranald’s father, was just such a man.

Winter Sunlight on Glencoe and Loch Leven ~ Copyright Jim Stewart

Archibald McDonald was born at Leeckhentium, on the southern shore of Loch Leven, Glencoe, Appin, in North Argyleshire, Scotland, on February 3rd, 1790. [His paternal grandfather, Iain (or John) McDonald, had been one of the few male survivors of the Massacre of Glencoe** in 1692.] It is said that Archibald was well educated and studied the rudiments of medicine at the University of Edinburgh before immigrating to Canada as a member of Lord Selkirk’s Colony(4) at Red River (Manitoba) in 1813, where he assumed a considerable share in the management of the Colony’s affairs, in part because he could act as an interpreter between the overseers of the colony, who spoke English, and the settlers, who, like him, were native Gaelic-speakers. [Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771~ April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk and was part-owner of the Hudson Bay Company.]

After Lord Selkirk’s death in 1820, his executors administered the colony, and sought to reduce expenses by ending settlers’ subsidies and refusing to recruit new European immigrants. Consequently, population growth came largely through the retirement of fur traders and their native families to the colony, encouraged by the newly-formed Hudson’s Bay Company’s reduction of the number of its employees. In the spring of 1820 Archibald entered the service of the H.B.C., shortly after the union of the H.B.C. and the North West Company; in 1821 H.B.C. Governor George Simpson sent McDonald to the Columbia district, on the Pacific Northwest coast, where he first served as accountant at Fort George [Fort Astoria].

It was at Fort Astoria in 1823 that Archibald was married “according to the custom of the country”, to the princess Koale’zoa (also known as Raven or Sunday) (d. 1824), daughter of Chinook chief Comcomly, with whom he had one son, Ranald McDonald; Archibald married a second time in 1825, also according to the custom of the country, Jane Klyne, a Metis [mixed-blood] woman with whom he had twelve sons and one daughter.(5)

McDonald was one very busy man; we might even be tempted to call him an ‘over-achiever’. At the very least his resume` is impressive. The following information is taken from Archibald McDonald: Biography and Genealogy, an article written by William S. Lewis and published in the Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 1918 : “In 1824 Archibald McDonald was one of the clerks in charge of posts in the Thompson’s River District, also known as the Columbia District. He succeeded John McLeod, Chief Trader, at Kamloops in the Thompson’s River District, in 1826.(6) In July 1828 he accompanied Governor George Simpson of the H.B.C. on a canoe voyage from York Factory, Hudson’s Bay to Fort Langley, New Caledonia, where he succeeded James McMillan.(7) He remained at Fort Langley until the spring of 1833. While stationed there he inaugurated the business of salting and curing salmon for market. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 15, 1831, McDonald wrote: “Our salmon, for all the contempt entertained for everything outside of the routine of beaver at York Factory, is close up to 300 barrels.”(8)

In 1833 he suggested the idea of raising flocks and herds on the Pacific Coast.

McDonald left Fort Langley for Fort Vancouver and on May 1833 selected the site and helped lay the foundation of Nisqually House [near present-day Tacoma, WA.] In July of that year he accompanied William Connolly up the Columbia with supplies for the interior, for the purpose of proceeding overland to enjoy a furlough. He spent 1834-35 in Scotland. Returning in the spring of 1835, he took charge of Fort Colville in 1836.(9) McDonald was stationed at Fort Colville from 1836 to 1843. In 1842 he was promoted to Chief Factor. While in the Columbia River district, Archibald had charge of and was eminently successful in placing the land in cultivation, and acquiring and raising horses, cattle, sheep, etc. In a letter to John McLeod dated January 25, 1837, McDonald states, “Your three calves are up to 55 and your 3 grunters would have swarmed the country if we did not make it a point to keep them down to 150.”(10)

Writing in September, 1837, Rev. Elkanah Walker thus describes Archibald McDonald’s farming operations at Fort Colville:

“It was truly pleasing after being nearly half a year without seeing anything that will bear to be compared with good farming, to see fenced fields, houses and barns grouped together, with large and numerous stacks and grain, with cattle and swine feeding on the plain in large number. There is more the appearance of civilized life at Fort Colville than any place I have seen since I left the States, and more than you see in some of the new places in the States … Mr. McDonald raises great crops. He estimates his wheat this year at 1500 bushels and his potatoes at 7000 bushels. Corn is in small quantity in comparison with his other grains.”

While at Fort Colville, in the early forties, Archibald McDonald is said to have had many hundred acres under partial cultivation. His son, Benjamin, stated that his father had nearly five thousand acres of land under cultivation at one time in the vicinity of old Fort Colville. Mr. Jacob A. Meyers places the maximum of land in agricultural use by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the vicinity of Fort Colville at 2000 acres, including in this estimate hay lands some twelve miles distant in the neighborhood of the present town of Colville. The company also held six townships of pasture lands obtained from the Indians by treaty.(11) [In his later years, Archie’s son Ranald panned the creeks flowing into the Kettle River and Boundary Creek in search of gold; Ranald died on the Colville reservation in 1894 in the arms of his niece, Jenny Lynch, the daughter of his half-brother Benjamin.](12)

At Fort Colville, Archibald supervised the reconstruction of the old sawmill, said to have been originally built in 1826-9, and the first sawmill on the Pacific Coast north of California. The original roof boards of the old fort buildings, of mill-sawn lumber, and lumber for company boats, bateaux and other purposes came from this mill. McDonald also supervised the rebuilding of the gristmill on “Mill Creek” (now Meyers Falls of the Colville River).

During Archibald McDonald’s many years in the Northwest he made no less than 15 trips across the continent between 1812 and 1845. He also kept very accurate journals, describing the country as regards to topography, soil, timber, rivers, climate, etc., through plains and over mountains, from Hudson’s Bay and the Great Lakes to the Pacific.

On his retirement from the H.B.C. in 1844 he moved overland with his family to Montreal, where he resided for two years. He then moved to St. Andrews on the Ottawa River, where he purchased a large tract of land and established a permanent home. He called his residence “Glencoe Cottage” and here he continued to live until his death on January 15, 1853, at the age of 62 years. Sadly, he may have died believing that his eldest son Ranald had perished at sea, though according to Fred Schodt in Native American in the Land of the Shogun, “ … this was unlikely. On April 3, 1852, the month before he removed Ranald from his will, Archibald wrote to a relative in Ft. Colville: ‘From Ranald, the Hero of Japan, I had several letters since his withdrawal from Jedo (sic) – He sticks to the sea, and last sailed from London for Sidney. But I trust now he will prefer digging for gold in Australia to the precarious and uncertain life of a sailor.’ ”

In the business of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archibald displayed great initiative and energy, and, possessing also considerable executive and business ability, he was unquestionably one of the most capable chief traders in the Columbia River District. Moreover, Archibald McDonald was a likeable character. He was naturally of a kindly nature, and a most agreeable companion. During his many years in the Northwest he maintained an extensive correspondence with his contemporaries in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service. To visitors at his post he was a most courteous host. John McLean, writing in April, 1887, says, “We met with a most friendly reception from a warm hearted Gael, Mr. McDonald.”(13) Reverend Elkanah Walker, in his Journal, under date of September 17, 1888, writes of his arrival at Fort Colville, “Received a cordial welcome from Mr. McDonald and lady.” Subsequent pages of the Journal record many courtesies and kindnesses of the Hudson’s Bay Chief Trader.(14)

His family relations were ideal, and he at all times displayed a patient and earnest regard for the spiritual and temporal welfare of his children, to all of whom he gave such educational advantages as his means and the times permitted. “It is high time,” he writes, “for me to see and get my little boys to school – God bless them – I have no less than five of them all in a promising way.”(15) A highlander born and bred, Archibald McDonald was in the best sense of the term “a gentleman of the old school,” a man utterly fearless, and of greatest personal integrity and honor. McLeod in his Peace River (pp. 117, 91) describes him as “a gentleman of utmost suavity of spirit as well as form.”

“As the twig is bent, so grows the tree.” It seems that in this, Ranald MacDonald had a superior role model in the form of his father.

To be continued … ~A.M.Y.~~~

(1)The Legacy of Scottish Highlanders in the United States ~Michael Newton 2001 (2)Ibid. [3]Mike Dunlap, from the upcoming book, “New World Celts: Voyage to America”[4]Thomas Douglas (June 20, 1771 — April 8, 1820) was the 5th Earl of Selkirk[5]Jean Murray Cole, Dictionary of Canadian History On Line[6]McLeod’s Peace River[7]See Archibald McDonald’s Journal; McLeod’s Peace River[8]Washington Historical Quarterly, i, 265, July, 1907.[9]Washington Historical Quarterly/, ii, 254, April, 1908;[10]Ibid [11]Lieutenant Johnson gives the cultivated land in the immediate vicinity of the fort (1841) as but 130 acres. U. B. Exploring Exp., iv, 443.[12]Washington State History, Native Americans in Ferry County[13]John McLean, Notes of a Twenty-Five Years’ Service in the Hudson’s Bay Territory [14]Reports of the U. S. (Wilkes Expedition (1841), IV, 443, 454[15]Washington Historical Quarterly, ii, 163, January, 1908

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Ranald MacDonald’s World – Roots – Archibald and the H.B.C. Fur Trade

November 1st, 2010

文・写真:谷口雅春 / 2010年11月1日

なんと途方もない聞き書き本が僕たちにもたらされたことだろう。

前稿で露口啓二が紹介したように、このたび利尻町立博物館学芸課長の西谷榮治さんが著した「利尻の語り」は、1986年から23年もの長きにわたって北海 道利尻町の広報誌「広報りしり」に連載されてきた、島民やゆかりの人々の聞き書きを再編集したもの。B5版464ページの大部に、146人の語りと、内容 にちなむ写真がおさめられている(編集者西村淑子さんの丹念な仕事が偲ばれる)。

例えば伊勢から渡った海女たちの暮らし。ニシンの爆発的な大漁や、クジラが浜に寄り付 いた挿話。樺太との深い関わり。集落ごとの祭りや演芸会、相撲大会に血肉を踊らせた青年団の活動。盆や節句、あるいは学び舎の行事の数々。各地からの開拓 移住のあらましに、襞のように入り組んだ地名や地誌の言い伝え…。明治、大正、昭和にまたがるおびただしい主題が、欄外の注釈が欠かせないような独特の言 い回しで展開されていく。話し言葉をていねいになぞる筆致も魅力だ。

利尻に本格的に和人が移り住んだのは安政年間(1854〜1860)のことだという。 その前史として17世紀後半にはすでに松前藩の場所経営があり、時代を下れば今号のカイでもふれた、津軽や秋田藩士たちによるロシアへの備えがあった。北 海道本島と共通する水産資源と地政学的意味によって、利尻島の近代は急駆動される。内地とは比較にならない厳しく複雑な気候をまとった利尻山 (1721m)が海底から一気にそびえ、ごく限られた土地と海で繰り広げられてきた濃密な歴史は、この島の輪郭に北海道史の縮図や、「もしも世界が100 人の村だったら」といった思考モデルを誘うかもしれない。しかしそんな紋切り型のまなざしは、語りのディテールの強度の前に恥じ入るばかりだろう。本書に 満ちているのは、郷愁の下味がついた北方イメージの断片などではなく、記(しる)されることもなくひっそりと記憶に眠っていた、ひとりひとりの固有の身体 から編み上げた利尻島の風土であり、なまなましい人生そのものなのだ。

カイにも、まだ9回にすぎないが井上由美が連載している聞き書きシリーズ、「北海道の 物語」がある。聞き書きにおいて話し言葉から書き言葉への変換は、書き手をつねに正解のない問題の前に立ち止まらせる。本書からもその困難との折り合いの 軌跡が浮かび上がるが、464ページというボリュームは、口語と記述をめぐる日本語の成り立ちまでも意識させるだろう。読み進みながら想起したのは、水村 美苗の「日本語が亡びるとき」(筑摩書房.2008)だ。水村は、19世紀に「西洋の衝撃」を受けた日本の知識層が、その現実を語るために日本語の古層を 掘り返し、日本語のあらゆる可能性をさぐりながら「出版語」を作りだしたこと(その言葉によって日本の近代文学は立ち上がった)。言文一致とは、単に口語 を書き言葉に移した取り組みではなく、幕末から明治の東アジアの激動の中で考案され磨かれてきた壮大なプロジェクトだったこと。そうした史実に無頓着なま ま、緊張感をなくした日本語はインターネットの時代に英語に飲み込まれようとしていることをスリリングに論考する。同次元で「利尻の語り」には、亡びゆく 土地の記憶をなんとかつなぎ止めようとする、現代日本語の格闘が浮かび上がっているともいえる。

マネーやイメージは根を持たないが、人間は土地を離れて生きることができない。20年 以上の歳月をかけ、これからもなお続く聞き書きは、利尻で生まれ育ち東京で学び、利尻に根ざし続けることを選んだ西谷さんにしかできない仕事だろう。受け 止める僕たちは、亡びるものへの感傷などで視界を汚してしまう前に、語りのリアルな細部から、北海道がほんとうに守るべきものや受け継ぐべき価値をしっか りとまさぐっていきたい。

(自費出版。3,360円で実費発売。問い合わせは利尻町立博物館 tel:0163・85・1411へ)

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on 西谷榮治 『利尻の語り』 を読む

October 18th, 2010

利尻昆布漁

今年は天候に恵まれず、昆布漁が少なかった。

7月中旬から始まった昆布漁。

海が凪ぎても、雨・霧。

晴れても時化る海。

晴天と凪の組み合わせが少なかった。

明日は昆布採りになるかも、で、朝3時頃から起きている漁師。

昆布かウニ漁かは、朝に決まる。

天気予報しながら、昆布の製品化で夜遅くまで作業。

夏は、体力と気合との勝負と、漁師が言っていた。

Harvesting Konbu. (Photo by E. Nishiya.) Harvesting Konbu. (Photo by E. Nishiya.)

Every autumn the strong winds and the ocean waves bring “Rishiri konbu” to the shores. The competition among the fishermen (and fisherwomen) is fierce.

You’ve got to gather better and more konbu than the others!

The hearty men and women of Rishiri go out to the ocean and to the beaches,

oblivious to the blustery fall weather.

Rishiri Island konbu is reputed to be the best-tasting konbu in Japan!

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Rishiri Island in the Autumn

October 14th, 2010

ラナルド・マクドナルドは1824年、毛皮交易商のスコットランド人の父と、アメリカ先住民の母との間に生まれる。出身はアメリカオレゴン州アストリア。幼いころから日本に対して強い興味があり日本へ渡る。今では、日本で最初のネイティブ英語教師として知られている。

1848年、当時24歳のマクドナルドは遭難を偽装し当時鎖国中であった日本への入国を果たし、北海道の焼尻島へ上陸した後、利尻島へ上陸した。この利尻 島でアイヌ人とともに数日間暮らした後、密入国の疑いで長崎に送られ拘禁されたが、彼の誠実な人柄と高い教養が認められ、徳川幕府から、西山郷に英語教室 開設を許可されている。ここで、アメリカへ送還されるまでの半年間の間、出島で働く14人のオランダ通詞たちに英語を教えたとされている。マクドナルドが 来日する以前は、オランダ語を経由せず直接的に英語を教える講師はいなかったので、彼が初の英語教師となった。教え子の中には、ペリーとの交渉で活躍したことで有名な森山栄之助などがいる。またマクドナルド自身も日本への関心から日本語を学び、日本初の英日単語帳である『英語対照語彙集』を残した。その現物が、ビクトリアのB.C.州立図書館内に保存されている。

その後、1849年、マクドナルドはアメリカへ戻ったが、日本での日本人のマクドナルドへの扱いは丁寧であり、マクドナルドもまた、死ぬまで日本に好意的 だったという。帰国後は日本の情報をいち早くアメリカへ伝えた。アメリカ議会に「日本社会は法治国家であり、日本人は礼節正しく民度も高い」と、日本が未 開社会ではなく高度な文明社会であることを伝え、のちのアメリカの対日政策の方針に少なからず影響を与えた。日本では主に英語教師としてだけ有名である が、アメリカの歴史ではかなりの重要性を占める人物として、研究や紹介の書籍が多く公刊されている。中でも日本滞在中に日本について鋭く観察した事を元に して書いた『日本回想記』は有名である。

マクドナルドは1894年70歳で人生を終えるが、病床で「Soinara(=さようなら)、my dear、Soinara」と傍にいる姪に呟いて息絶えたと言われており、彼の墓石には「SAYONARA」 の文字が刻まれている。マクドナルドの生涯を通し、それほど日本への好意と関心があったようで、日本では利尻島の上陸地点と長崎市内諏訪神社の近くにマク ドナルドの記念碑があり、現在も親しまれている。又、アストリア市内の史跡公園には、日英両語で「マクドナルド生誕の地」と記された記念碑が建てられてい る。

Thank you – State of Oregon Japan Representative Office.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on 日本で最初の英語教師 Ranald MacDonald

July 18th, 2010

リシリヒナゲシの咲く麓から

エゾニュウ群生 島を周回する道路際や海岸草原で見られるエゾニュウ。

背が高いことから、目立つ。

今年は6月末の暑さからだろうか、いつもより多くエゾニュウが咲いているようだ。

Ezo-nyuu – you see them in the grass fields and on roadside along the coastline of Rishiri Island. Because of their height, they stand out and are quite noticeable. This year more Ezo-nyuu than usual can be seen. I wonder if that is because of the hot days we had on the island in late June ? ~~~ Eiji Nishiya, FOM Rishiri, Japan – Mt. Rishiri in the background

Towering above the surrounding lush summer herb growth stands the hollow-stemmed monster known locally as Ezo nyuu (and to botanists as Angelica ursina – “bear’s angelica”). These plants appear at the height of summer, a potent reminder that the longest days are past and that, despite the heat, autumn is not far around the corner.

The umbel (flower head) of Angelica ursina has many small white flowers on thin stems attached to a main stalk. Their flowers fade in a matter of weeks, but their weathered, dried stems are strong and persist even into winter, when they rattle and buzz as the wind vibrates them, scattering their tiny seeds.

This tall perennial can be found in damp, cool places, along roadsides, around marshland edges and in sunny woodlands, wherever there is plenty of moisture. It grows in central and northern Japan, in China, and in areas of Russia surrounding the Sea of Okhotsk.

Whereas many members of the Angelica family may only grow to heights of between 50 cm and a meter, the bear’s angelica is a monster – the largest in the family – reaching a height of 3 to 3.5 meters!

Since he came ashore on or about July 1, 1848 – mid-summer – no doubt Ranald saw plenty of these giant Angelica ursina growing in the grass fields of Rishiri Island.

Photos by Eiji Nishiya, FOM Japan

~~~~~

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Ezo nyuu (Angelica ursina – “bear’s angelica”) of Rishiri

July 15th, 2010

150 years ago, the world had yet to discover Japan, and the people of Japan had never seen America …

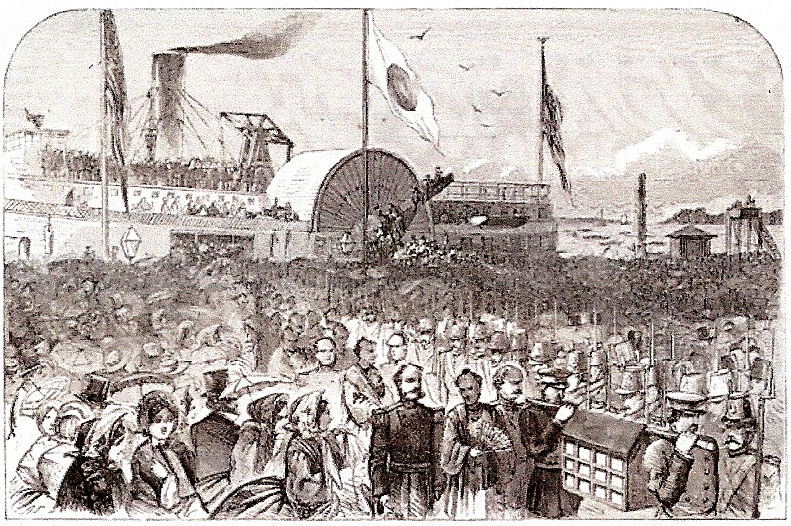

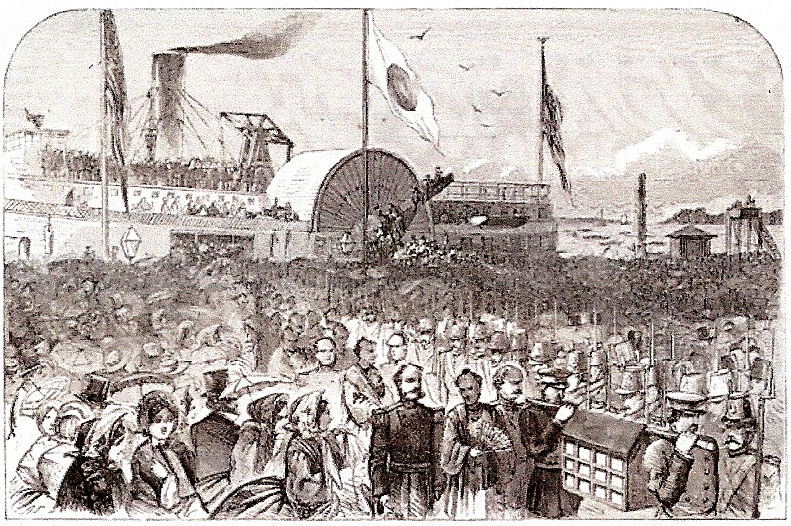

In the summer of 1860, before the Civil War erased all thoughts of international affairs from America’s mind, the Japan’s Tokugawa government sent its first diplomatic mission to the United States: a group of 77 samurai whose purpose was to exchange the instruments of ratification of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1858). The agreement opened the ports of Edo and four other Japanese cities to American trade, among other stipulations. In the years before the Civil War, the Japanese visitors captivated the American people and the press. Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860 Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Throughout their seven-week tour, the guests from Japan were greeted with great excitement, if not outright curiosity given their “exotic” dress and demeanor. Everywhere they went, they were met by overflowing crowds, and impressive parades were staged in their honor. The historic visit was widely covered in the American press of the day, which relished recounting every detail of the visits made by these exotic visitors. In fact, these Japanese envoys from across the Pacific became celebrities who captivated much attention across a nation that had yet to experience the outbreak of the American Civil War. This remarkable encounter of cultures was described in the June 11, 1860 edition of The New York Times as “… an event which, if it have any significance at all, involves consequences the most momentous to the civilization and the commerce of the world for ages to come.”

USS Powhatan carrying the First Japanese Embassy to America, circa 1860. Woodblock print, ink and colors on paper. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, CA (The U.S. frigate Powhatan was the so-called “Black Ship” formerly under the command of Commodore Perry)

This momentous event was not only a first for Japan, but for the West as well. Before the Japanese Embassy’s arrival on American shores, no Western country had ever received a diplomatic mission from East Asia. The significance of this great honor was not lost on the fledgling American republic. Congress adjourned for their arrival at the Navy Yard, while a crowd of 5,000 gathered to greet the samurai at the docks. Another 20,000 Washingtonians – Washington’s population at that time was about 75,000 – cheered along their route to the Willard Hotel, where the samurai would lodge during their stay. Men and boys climbed trees to get a better look as ladies tossed flowers from crowded, second-story windows.

Vice Envoy Muragaki described the scene in his private journal:

“What immense crowds there were! The streets were like seas of human beings; the windows and balconies were thronged with people eager to get a glimpse of the procession. I could not help smiling at the wonder in their eyes, which reached a culminating point when they caught sight of our party wearing costumes that they had never seen before or even dreamt of. I might say that the whole procession seemed to the people of Washington to be a scene out of fairyland, as, indeed, their city appeared to us.

It was however, not without a feeling of pride and satisfaction that we drove, in such grand style, through the streets of the American metropolis, as the first Ambassadors that Japan had ever sent abroad, and that we witnessed the enthusiastic welcome accorded to us by the citizens.”

Herman Melville called Japan “impenetrable” in Moby Dick (1851), and predicted that “(if) that double-bolted land, Japan, is even to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone to whom the credit will be due; for all ready she is on the threshold.” Less than three years later Commodore Perry’s steam-powered “Black Ships” [which included the U.S. frigate Powhatan] lowered their anchors in Edo Bay in 1853 and Japan’s official policy of national isolation, which had been followed for over two centuries, did indeed come to an end.

When I Googled “1860 Japanese ambassadors to America” over 90,300 results appeared. Of course I did not visit each and every website, but I did peruse the first four pages totaling just under 40 links. For Japanophiles the very idea that 90,000+ pages were devoted to one subject, e.g., the first Japanese embassy to visit America, is gratifying. For Friends of MacDonald members, however, the sparkles of delight are definitely muted; nearly every web article I inspected lovingly pointed out that Commodore Perry had “opened” Japan a mere 7 years before the official Japanese embassy visit, but none – NOT ONE – made mention of the fact that it had been Ranald MacDonald’s efforts – his design, if you will -that had facilitated the success of America’s first official contact with Japan, but Ranald had clearly articulated his intent, to wit:

“Wonder in an ocean of wonders! – to us, on its opposite shore, gazing, searching into the far, far offing, it was ever an object of intense curiosity. What of such people? What of their manner of life? What of their unrivalled(sic) wealth with its gleam of gold and things most precious? What of their life, social, municipal and national? What of their feelings and tendencies – if any – toward association or friendly relations with other people, especially us, neighbors of their East?

These and such like questions and considerations ever recurring; the subject, oft, of talk amongst my elders … entering deeply into my young and naturally receptive mind; breeding, in their own way, thoughts and aspirations which dominated me as a soul possessed. I resolved, within myself, to personally solve the mystery, if possible, at any cost of effort – yea, even life itself.

Satisfied in my own conscience with my purpose, I never abandoned it. That purpose was to learn of them; and, if occasion should offer it, to instruct them of us.” ~~ Ranald MacDonald, The Narrative of His Life, 1824-1894; pg.131 (annotated and edited by Wm. Lewis & N. Murakami)

And so he did. And if Ranald had not had the opportunity – and the audacity – to instruct several, bright Japanese students in the complexities of the English language – among them the Emperor’s eventual chief interpreter to Commodore Perry, Einosuke Moriyama – who knows how America’s initial foray into Japan would have turned out?

***

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Samurai in Washington D.C.

July 11th, 2010

The day was fair, the turn-out was gratifying and the conversation lively at the annual membership meeting of the Friends of MacDonald held in Astoria, OR over the weekend. We greeted many old friends and welcomed several new members while enjoying a delicious lunch at the “Baked Alaska” restaurant (shameless plug) on the waterfront overlooking the wide mouth of the Columbia River and the blue-green hills of Cape Disappointment and Chief Comcomly’s Chinook territory in Washington — the same view eyed by the likes of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1805-06 as well as Ranald’s father, Archibald McDonald in November of 1821, the year he arrived at (then) Fort George.

We were honored to welcome Consul General of Japan in Portland, Takamichi Okabe and his wife, Kozue. According to Richard Read of the Oregonian newspaper, Mr. Okabe spent three months in Baghdad as an involuntary “guest” of Saddam Hussein during 1990, when Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait. [He had been serving as first secretary in Japan’s embassy in Kuwait.] During his next foreign assignment – in Kenya – Mr. Okabe and a colleague braved warfare in Somalia to investigate opportunities for humanitarian aid there. Later in Nepal, Mr. Okabe was posted in Kathmandu when members of the royal family were massacred at the palace. Most recently Mr. Okabe served four years as Consul General of Japan in Auckland, New Zealand. In Portland, he is joined by his wife, Kozue, and we all hope that Mr. and Mrs. Okabe will have the opportunity to enjoy the peace and beauty of the Pacific Northwest.

FOM was happy that Mac Burns, Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here: http://www.astoria200.org/ . If you have never visited Astoria, FOM encourages you to do so – it is a sleepy little coastal town with a lot of secrets and surprises, not to mention a rich history. Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here: http://www.astoria200.org/ . If you have never visited Astoria, FOM encourages you to do so – it is a sleepy little coastal town with a lot of secrets and surprises, not to mention a rich history.

Mr. Tadakazu Kumashiro, Charter Member of the Friends of MacDonald, was also in attendance. After his retirement, Mr. Kumashiro, or “Kuma” (the Bear) as he likes to be called, joined the Peace Corps in 2001 and was stationed in Namibia for a couple of years working for the Namibian government where he promoted AIDS education by visiting schools. Kuma-san gave talks to students, teachers and school principals about what they should be doing to prevent an AIDS pandemic. Kuma-san reports that he had to be hospitalized himself four times while he was there – probably, he noted, because of the unfamiliar germs he encountered. Mr. Kumashiro rather depreciatingly says he thinks he became ill because of his “old age” – he was 67-69 at the time – but having met him myself I have to say he is one of the most vigorous and energetic “seniors” I have ever met [both mentally and physically].

A big “thank you” to Jim Mockford for bringing his laptop so the group could access the new web page. It was the first time most of the FOM members had seen it (we hope it won’t be the last time!) We all appreciated that the Baked Alaska staff worked so hard to make sure their wireless network was workable for us. And we missed the presence of Bruce Berney, who was back in Portland celebrating his grandson’s birthday.

During the meeting an interesting, if not recurring, question was presented by Consul General Okabe, e.g., what was the status of Ranald MacDonald’s “citizenship” at the time of his landing on Rishiri Island in 1848? A second comment [also in the form of a question] was presented by Mr. Okabe and was definitely food for thought – was Ranald MacDonald really the first teacher of English in Japan?

Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600 Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600

The Consul General’s second question referred to one William Adams, who, as the British pilot major of the Dutch trading ship Liefde (“Love” or “Charity”) landed off the island of Kyushu in April 1600. [The true story of Will Adams was the basis of the romantic novel Shogun, written by James Clavell and published in 1975; Adams’ adventures were also documented in the historical novel Daishi-san written by Robert Lund in 1961.] According to one source “ … soon after Adams’ arrival in Japan, he became a key advisor to the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu and built for him Japan’s first Western-style ships. Adams was later the key player in the establishment of trading factories (in Japan) by the Netherlands and England. He died in Japan at age 55, and has been recognized as one of the most influential foreigners in Japan during this period.”

William Adams – known in Japan as Miura Anjin – may have been the first Englishman [Briton] to set foot in Japan; from historical information [including writings from Adams’ own journal] it seems likely that it was the Anjin who needed an interpreter [the ever-present Portuguese Jesuits, in this case] to make himself understood. Prudence dictates that circumstances – and the Japanese people – taught their language to Will Adams, rather than the other way around.

Regarding Ranald MacDonald being the firs t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there. t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there.

***

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on July 2010 ~ FOM Annual Meeting

|

|

|

Harvesting Konbu. (Photo by E. Nishiya.)

Harvesting Konbu. (Photo by E. Nishiya.)

Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Landing of Japanese Embassy at Navy Yard in Washington, DC, May 1860

Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here:

Executive Director of CCHS was able to take time away from his busy schedule to attend the meeting. Mac, who was fresh off the “Goonies 25th Anniversary” celebration the week before, noted that over 100 Goonies fans showed up for the grand opening of the Oregon Film Museum in Astoria the previous Saturday, and mentioned that people had come from all over — France, Japan, and from across the United States. Mac also passed out buttons and other information about the upcoming “Astoria 1811-2011 Bicentennial Celebration” happening next year. A link to that website can be found here:  Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600

Map of Japan drawn by William Adams, circa 1600 t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there.

t American to “set foot in Japan” [the way Will Adams was the first Englishman to do so] we know this just isn’t so. There were Americans who had visited Nagasaki while in the service of the Dutch during the late 1700’s. In the mid-1800’s there were scores of American whaling ships in the Sea of Japan, and historical record tells of some crew members that had either been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast or had deserted their vessel to seek their fortunes ashore. As far as is known, however, Ranald MacDonald was the first American to intentionally go to Japan for the express purpose of learning about the Japanese people and their language and to teach English to them, and to perhaps ‘work’ as an interpreter. As to the question of Ranald’s citizenship, regardless of the fact that Fort George was under a British flag in 1824, it cannot be denied that half of Ranald’s DNA came from a Chinook Indian mother, a fact that made him a truer “American” than any geographical accident of birth. Later in his life, through both choice and residence, MacDonald became sufficiently “American” enough to justify that we may say that Ranald MacDonald was the first American to leave his mark upon the people and the nation of Japan, and the first native-English-speaking individual to teach the English language there.