To help us appreciate the First Peoples of the Columbia River Basin …

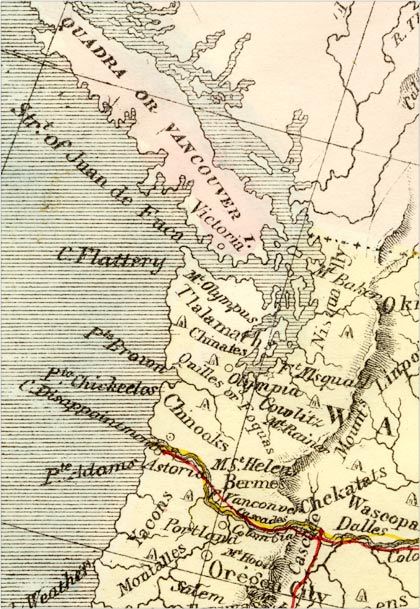

(Chinook, from Tsinúk, their Chehalis name). The best-known ‘tribe’ of the Chinookan family claimed the territory on the north side of the Columbia River from its mouth to Grays Bay, a distance of about 15 miles, and north along the seacoast as far as the north part of Shoal-water bay, where they were met by the Chehalis, a Salish tribe. The Chinook were first described by Lewis and Clark, who visited them in 1805, though they had been known to traders for at least 12 years previously(1) ~

“… This Chin nook Nation is about 400 Souls inhabid the Countrey on the Small rivrs which run into the bay below us and on the Ponds to the N W of us, live principally on fish and roots, they are well armed with fusees and Sometimes kill Elk Deer and fowl. our hunters killed to day 3 Deer, 4 brant and 2 Ducks, and inform me they Saw Some Elk Sign. I directed all the men who wished to See more of the main Ocian to prepare themselves to Set out with me early on tomorrow morning. The principal Chief of the Chinnooks & his familey came up to See us this evening …” [Clark, November 17, 1805] “… found maney of the Chin nooks with Capt. Lewis of whome there was 2 Cheifs Com com mo ly & Chil-lar-la-wil to whome we gave Medals and to one a flag. …” [ Wm. Clark, November 20, 1805 ]

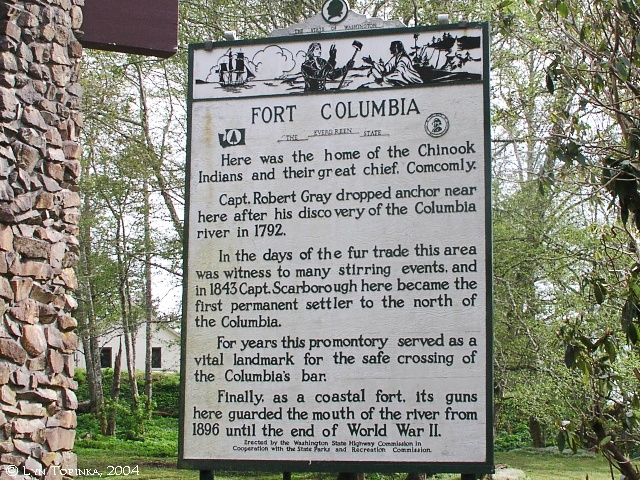

Com’comly, grandfather of Ranald and the principle Chinook Chief of the time, received the Lewis and Clark expedition hospitably when it emerged at the mouth of Columbia River in 1805, and when, in 1810, the J.J. Astor Expedition arrived to take possession of the region for the United States, Com’comly cultivated a close friendship with the pioneers, even giving his daughter [Ilchee] as wife to Duncan McDougal, a Canadian fur trader who was at their head and who took part in the founding of Ft. Astoria in 1811.

Yet Com’comly may have been an accomplice in a plot to massacre the garrison and seize the stores. When a British ship arrived in 1812 to capture the fort at Astoria, Com’comly, with 800 warriors at his back, offered to fight the’ enemy’. The American agents, however, had already made a peaceful transfer by bargain and sale, and gifts and promises from the new owners [the North West Company] immediately made Com’comly their friend.(2) Writing in Aug., 1844, Father De Smet(3) states that in the days of his glory Com’comly, on his visits to Vancouver, would be preceded by 300 slaves, “and he used to carpet the ground that he had to traverse, from the main entrance of the fort to the governor’s door – several hundred feet – with beaver and otter skins.”(4)

The Chinookan nation was one of the most powerful native groups in Oregon. It included those tribes formerly living on the Columbia River, from The Dalles to its mouth (except a small strip occupied by the Athapascan Tlstskanai), and on the lower Willamette as far as the present site of Oregon City, Oregon. The family also extended a short distance along the coast on each side of the mouth of the Columbia, from Shoalwater bay on the North. to Tillamook Head on the South.

The region occupied by Chinookan tribes seems to have been well populated in early times. Lewis and Clark estimated the total number at somewhat more than 16,000. In 1829, however, there occurred an epidemic of unknown nature, which, in a single summer, destroyed four-fifths of the entire native population. Whole villages disappeared, and others were so reduced that they were, in some cases, absorbed into other villages. It can be assumed that it was the result of contact with a “white man’s” disease for which they had no immunity. The epidemic was most disastrous below the Cascades. In 1846 Hale estimated the number below the Cascades at 500, and between the Cascades and The Dalles at 800. By 1854 Gibbs gave the population of the former region as 120 and of the latter as 236. They were scattered along the river in several bands, all more or less mixed with neighboring stocks. In 1885 Powell estimated the total number at from 500-600, for the most part living on Warm Springs, Yakima, and Grande Ronde reservations in Oregon.

Most of the original Chinookan bands had no special tribal names, being designated simply as “those living at (place name)” This fact, especially after the epidemic of 1829, made it impossible to identify all the tribes and villages mentioned by early writers. Their language served as the basis for the Chinook Jargon which became the principal means of communication for the Indians from California to the Yukon, as well as trappers, traders and the majority of other individuals living and surviving in the territory.(5)